Books I’m reading this year…

That feeling where you’re looking forward to an early night so you can read your book. And then you remember you finished it the night before…

… That’s basically how my first book of 2024 went. I really enjoyed it.

In an attempt to read more, I tracked all the books I read in 2022, first in a twitter thread and then later in a long blog post here. I didn’t do it in 2023 and found I missed looking back through it. So, 2024 is a new start. I’m not aiming for a particular number, reading is for me pure pleasure. There is so much that could be read and life is so short, so this page is mostly for me. But in case anyone else finds my rather random book taste worth a look, the 2024 reading thread is now live.

44. As I walked out one midsummer morning, Laurie Lee

Another English classic, the story of a young penniless boy who took his violin under his arm and walked, first to London and then to Spain in 1935. The quality of the writing makes this a stand-out, and, as Robert MacFarlane makes clear in the introduction there is a very obvious parallel with Patrick Leigh Fermor’s memoir of central and eastern Europe, also experienced by a young man (if of a subtler higher class than Laurie Lee), on foot in the mid 1930s. Patrick Leigh Fermor’s “A time of gifts” that narrates his accounts is one of my favourite books of all time, I absolutely enjoyed the spare prose of Laurie Lee too, both had the gift of being able to sum up in beautifully compact forms, the experience of being on a strange land and simply noticing, absorbing, experiencing a new landscape.

Many people have been inspired to repeat parts of Laurie Lee’s journey, or variants of it, like Alastair Humphries whose book on the experiment I read last year. I suspect few manage to actually experience Spain similarly, the book is as much about a time as a place, it’s hard to imagine a tourist free Spain, nor to appreciate how poverty stricken the country was. Similarly in England, few now appreciate probably how hard life was for the tramping class, in this sense, the book is also an important historical account.

I only now realise just how many books about walking I have read this year, perhaps it’s a substitute for living in a crowded city, in a low-lying land and not giving myself the time to range wider and explore on foot?

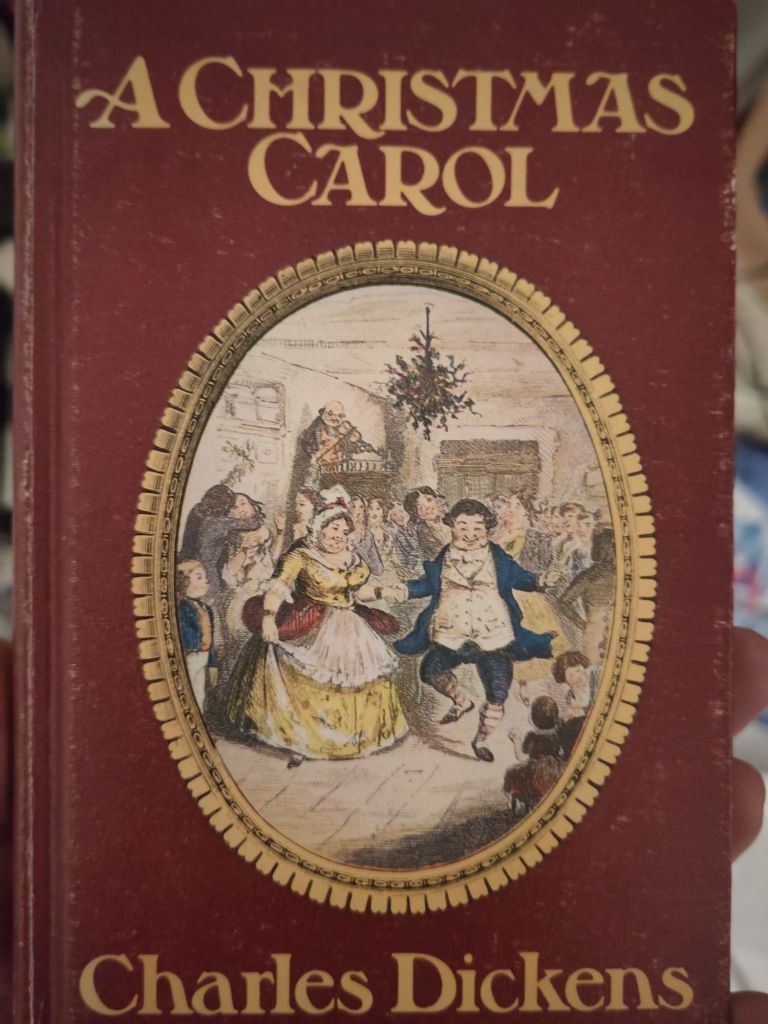

43. A Christmas Carol, Charles Dickens

What can I say? It’s a classic. I’ve read it every year at Christmas for the last few years. I usually listen to a radio play version from the BBC – a co-production with the BBC singers as chorus that is quite brilliant, while I wrap presents. The play was unavailable this year so I listened to an abridged version, re-reading the book straight afterwards to see what was cut out, it’s quite clear it’s really a very short novella with padding, in that 19th century way that I think makes us in the 21st century often a little impatient.

Last night we watched the classic film Elf, on a similar theme of Christmas redemption, the news which flashed past when we finished it was of a certain incoming US president and his desires to annex various other sovereign countries. It is pleasant to be able to ignore those unpleasantnesses at Christmas but there’s a warning in this book too: “This boy is Ignorance. This girl isWa t. Beware them both, and all of their degree, but most of all beware this boy, for on his brow I see that written which is Doom, unless the writing be erased.”

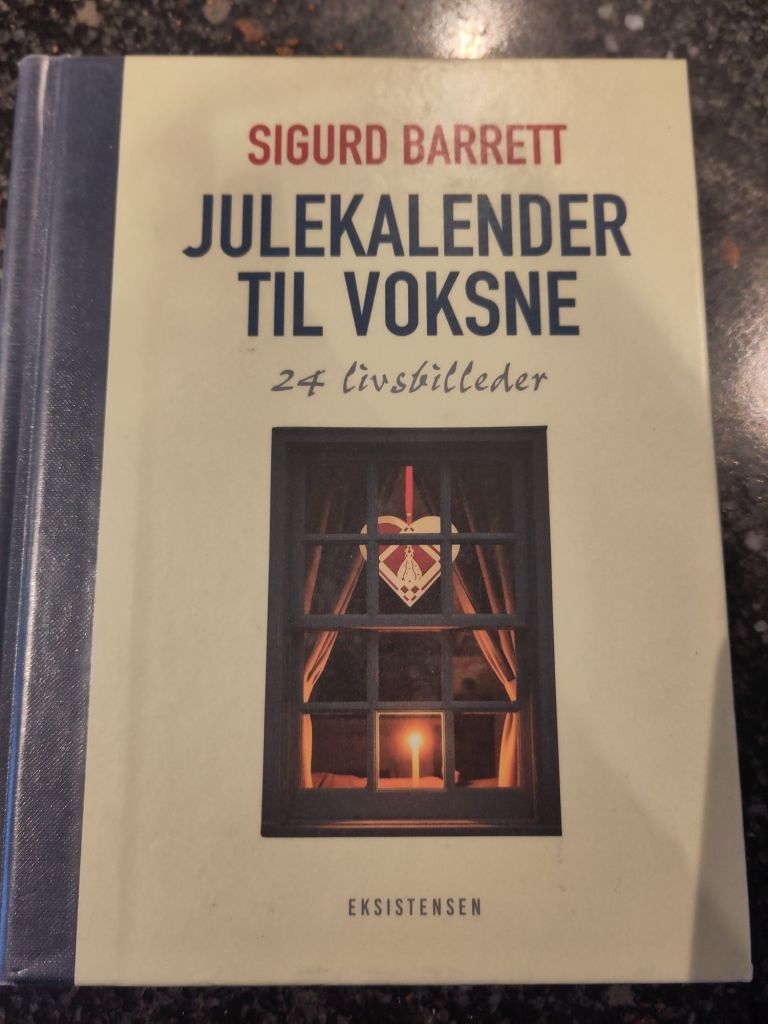

42. Julekalender til voksne, Sigurd Barrett

A collection of 24 short stories, each one a window into a person’s life by legendary children’s writer and presenter Sigurd Barrett, but this one is aimed at adults (I admit, I read on ahead). I really like this as an advent concept, and the stories are heartwarming and just edgy enough, and humourous enough, to avoid being overly sentimental. The harassed weather presenter being constantly asked about the likelihood of a white Christmas was particularly funny… Another piece from our librarian’s Christmas table..

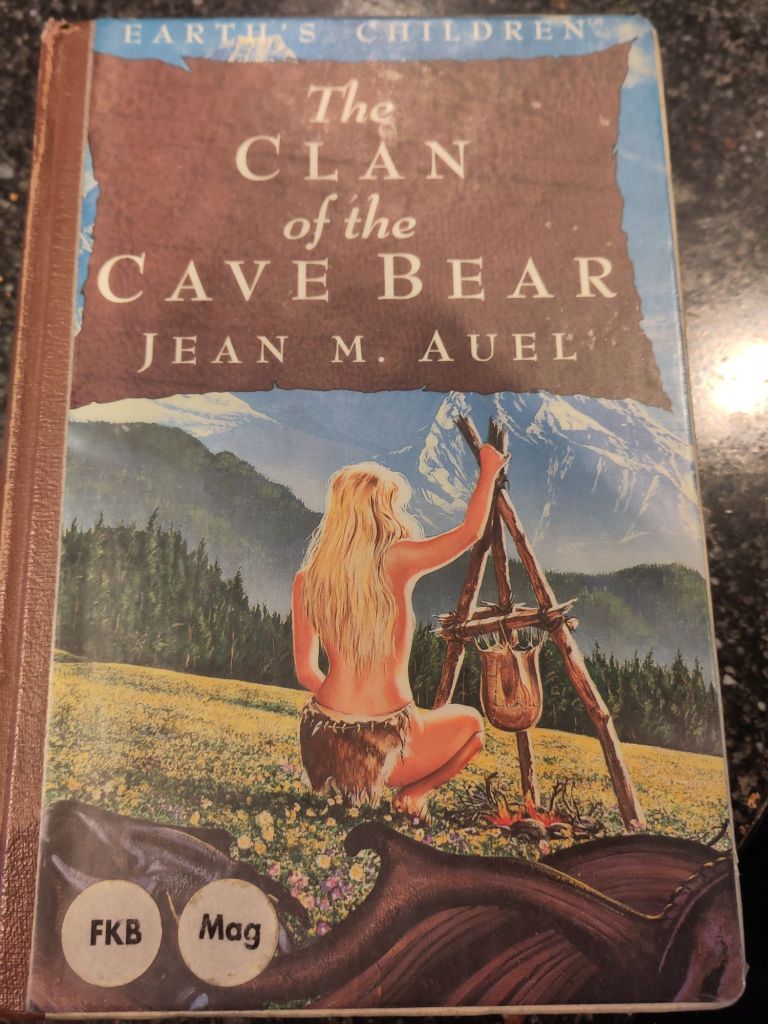

41. The Clan of the Cave Bear, Jean M. Auel

A bit of a classic of historical fiction this one, and I can see why. The story is fairly simple but compelling. The details of every day life in a small clan of Neanderthals who find, rescue and bring up an orphaned Cro-Magnon girl are really well brought out. It’s hard to believe that much of it is pure speculation, though certainly very well-informed speculation. Jean Auel did her research but the writing of it is fascinating. I would love to read an updated version incorporating all of the new science on Neanderthals since the late 1970s. I read the incredibly good Kindred by Rebecca Wragg Sykes a couple of years ago, which is a much more up to date overview of what we know now, and on the basis of this novel I think I may go back and re-read it to compare and contrast, overall from my memory it feels like much is still relevant.

Update: thanks to the Marvels of RSS, I found this podcast on AntennaPod that seems to address the points about new knowledge of prehistory including an interview with Dr. Rebecca Wragg Sykes.

Warning, there are some rather brutal scenes of violence and sexual assault in the book, though in general the atmosphere is rather homely.

40. At Christmas we feast, festive food through the ages, Annie Gray

A lovely way to get into Christmas – this was picked up from the same Christmas table at my local library as number 39. I think all families have their own traditions at Christmas, according to this book, some of them have very long roots indeed, though most are surprisingly recent. Annie Gray is a good historian and it is a fascinating journey, though rather English heavy. She states on several places that Christmas is a typically British, actually English, festival, but living in Denmark as I do I rather disagree. And in fact she acknowledges in several places that many english traditions come from Germany or have similar continental associations without going into the details. It would be nice to see the UK embrace it’s European identity for a change. This is a common failing in English history books though, so I can’t really blame her, and I very much respect her clear acknowledgement of the role that slavery, appalling, barbaric and cruel, played in making sugar so accessible and so much a part of Christmas. Not to mention the discussion on the role of servants, wealth and access to land, game and resources that drove the great differences between the Christmas of the rich and poor, and then of course, as england became more socially equal, the burden laid on women to fill the gap and prepare great complex feasts for the whole family.

Overall, a nice read but one that left me hungering for more detail, but a good one for getting into that Christmas mood.

39. Twelve days of Murder by Adreina Cordana

Let Jólabókaflóðið commence ..

This is a detective novel that’s slightly hard to classify , not quite hard enough to qualify as Scottish noir, but still a little too hard to be entirely a hyggekrimi. Nonetheless, a very compulsive read. I picked it up from the Christmas table in my local library at around 6pm, started reading it at 10pm and was done by 1.15am. Not sure quite what I’d planned to spend my evening on, but a nice finish to an evening celebrating Sinterklaas. It’s a classic set-up, a group of old university friends meet up 12 years after one of their number disappeared, a snowed in Scottish glen means no contact with the outside world and then the killing starts. The characters are pretty clichéd but the narrator is engaging and there are enough clues to get you to the end. Classic stuff, but just enough moral scruple to make you pause if murder should really be seen as entertainment. Christmas proper (or at least the pre-yuletide December panic) starts tomorrow.

38. Muriel Spark: a far cry from Kensington

I’ve only read one Muriel Spark before, the famous Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, this is another beautifully observed and atmospheric book, with a narrator, Mrs Hawkins and her group of friends, housemates and colleagues in the London of the 1950s. Another win for the Frederiksberg librarians*, I went in to return some books and came out with what can only be described as a haul. As the children immediately fell upon their choices, I took an hour out on a drab November Sunday and read this one cover to cover. It’s a charming tale, though with tragic elements. I really enjoyed the evocation of London at this time, it’s somehow hard to imagine that people led a life not dissimilar to ours, with humanity, sympathy, pragmatism, in spite of the glaring technological, social and political differences.

I suspect I shall be thinking about this one for a long time. I’d love to read more in the voice off this acutely observative narrator. Muriel Spark is definitely getting added to my hold list…

*As an aside, the library also currently has a whole set up of creative tables set up to make your own Christmas decorations out of old set aside books. I think it’s a brilliant idea, and perhaps not coincidentally, the library was actually really busy today. It warms the heart.

37. Timothy Snyder: Om Tyranni

For no particular reason…

I’m a huge fan of Timothy Snyder’s series, the making of modern Ukraine, and after seeing the point about not obeying in advance, I thought I’d check out the full volume from the library. It’s really worth a read, very short and easy to digest, even translated into Danish the chapters were often grimly entertaining (perhaps a tribute to the translator). It also reads as a kind of affectionate but ultimately rather clear-eyed view on European history from the 20th century and a very stark warning to us all.

36. Life as we have known it by Co-operative working women. Ed. Margaret Llewellyn Davies

This is a remarkable window into a time when the roots of the labour movement were planted. It’s brief little scraps of reminiscence, lists of library books, autobiography and a good solid introduction by Virginia Woolf. I can’t imagine how or why this thin little volume, first published in 1931 and reprinted in 1975 made it into my local library in Frederiksberg, Denmark, but my life is the richer for having read it. Not to mention that some of the things mentioned in here: the clothing club, the shocking tiny houses with no internal bathroom, the attitudes to women, still echoed in my early years in England. I found it on the table at the library, finished it in a oner. There are all kinds of lessons about organising, the time it takes for things to come through, the necessity of having a political voice, the importance of solidarity and education, that we shouldn’t forget, especially now when it sometimes feels our fundamental rights are under attack. As ever, thanks to our marvellous local librarians for this little gem.

35. The hermit of Eyton Forest, Ellis Peters

A brother Cadfael novel, because nothing is quite so escapist as reading about the investigations of a gentle but practical 13th century monk in civil war-torn England.

The mysteries are often rather simple to solve and I fear the harshness of life in those times is perhaps underplayed, but Ellis Peters has a marvellous gift for description, the land of the Severn around Shrewsbury, an area I used to know pretty well, is like another character in the books. This one has a satisfyingly just ending.

Given everything else going on in the world right now, I may read another Cadfael mystery next.

34. Dracula, Bram Stoker

A classic, which strangely I had not previously read, though it’s been on the shelf a while. I was inspired to pick it up by the enthusiastic report of elder kid’s friend and found it somewhat different to how I’d imagined it. In tone it’s very much of the Victorian age, and I’m unsure how modern audiences would really find it, but the characters of Mina Harker and Van Helsing shine through and it’s a gripping plot. Some startling parallels with Wifedom, book number 33.

Would recommend and will probably read again at some point…

33. Wifedom, Mrs Orwell’s Invisible Life Anna Funder

A remarkable book about a remarkable woman, pieced together from letters and interviews. It’s nominally a biography of Eileen Shaughnessy and George Orwell, but it’s also an examination of how her contribution, like that of many women through the ages, has been almost completely erased. It’s a meditation on society and patriarchy as well as reflections on how women let it happen and even encourage it. At times brutally honest, George Orwell does not come out of it well, at least as an individual. It’s a very thought provoking book and extremely persuasive. I shall look for her others, it’s very well written.

A remarkable book,

32. Not the end of the world, Hannah Ritchie

The main message of this book is summed up in the Introduction: The world is awful. The world is much better than it was. The world can be much better. Hannah Ritchie takes this message and applies it with plenty of illuminating graphics and well referenced data to 8 global problems. She argues for conditional optimism: an approach I appreciate because, unlike simply hoping for the best, it assumes humans individuals have agency and want to do the right thing. I’ve been deeply embedded in climate change research for many years and found the chapter I knew most about very convincing. This helps when the subject turns to biodiversity, air pollution, feeding the world and ocean plastic. Subjects I knew something about it Ritchie shows just how much developments in these areas have moved on and how quickly desperate situations can be turned around.

Optimistic, but never naive, she argues that we need to take a realistic look at the data we have, we need to collect more where it’s missing and we need to keep pushing for a better world. This is undoubtedly the book your climate doomer in the family should read, I would hope the family climate sceptic will also get much out of it, not least, just how many spinoff benefits restructuring our world for a sustainable future will have.

The scary part is that many of the trends, which are currently on the right tracks could very easily be undone in a multipolar and more insular world. As Afghanistan showed us, we can always go backwards too. This book is really a warning as to why we shouldn’t and how we need to keep pushing for a better future.

31. Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club, Dorothy Sayers

Adaptations of Peter Wimsey rarely get him right. They tend to depict him as a Woosterian idiot, a stereotype which it must be admitted, Wimsey himself occasionally plays up to in the books. In fact he is a shell-shocked aesthetic intellectual, deeply ambivalent about the role he plays in uncovering crimes, particularly where harm will come to others as a result. Sayers is thoughtful about the horror of the death penalty and the villains and crimes are frequently morally ambiguous. I’ve been reading Wimsey novels as a brain resetting brand of comfort reading for many years. Several of the books I’ve read many times, they are not as easy and undemanding as Christie, but they are literary and certainly more absorbing into their own world. It’s been a tough week and while sitting on the sofa watching terrible TV was tempting, I felt I needed something a little more brain nourishing, so this novel of Sayers’ was absolutely perfect. In fact it may be the only one of her books that I’d never read it before, so I was happy to find it on project Gutenberg.

A satisfying start to the weekend, finally allowing my poor brain some rest after a tiring week…

30. Gopler ældes baglæns (Jellyfish age backwards), Nicklas Brendborg

A book about aging and the scientific understanding of the process. The book is framed as helping us to think through the best ways to reduce the pace of aging and ensure a long and healthy lifestyle. It’s also full of fun anecdotes, amazing science and is highly entertaining to read.. I don’t think it’s been translated into English which is really a pity. I highly enjoyed it and will recommend to my Danish reading friends whole heartedly. It’s quite fascinating on everything from worms to mole rats and the titular jellyfish of course. Occasionally straying a little close to popular science where the evidence is a bit weak (the famous blue zones may reflect inadequate record keeping and pension fraud more than healthy lifestyles), the overall impression is one of a well researched and well-written summary of how to grow old slowly.

29. Four thousand weeks, Oliver Burkeman

A book I found so insightful that I’ll probably read it again straight away. It starts “The average human lifespan is absurdly, terrifyingly, insultingly short… Assuming you live to be eighty, you’ll have had about 4000 weeks”.

It ends: ” The average human lifespan is absurdly, terrifyingly, insultingly short. But that isn’t a reason for unremitting despair or for living in an anxiety-fuelled panic about making the most of your limited time. It’s a cause for relief. You get to give up on something that was always impossible… Then you get to roll up your sleeves and start work on what’s gloriously possible instead”.

Challenging the “busyness” orthodoxy and life affirming as well. A definite recommendation, especially to those of us with rather fewer than half of our 4000 weeks remaining.

28. Kvinde kend din økonomi (woman, know your finances), Sara Ophelia Møss

The second wave of feminism brought the classic Kvinde, kend din krop (woman know your body) to Danish bookshelves. Now the 5th (I think?) wave is very much focusing on financial empowerment of women, at least in Denmark, so this slightly strange sounding title fits into a long tradition. It’s very well written covering every stage of a woman’s life (and is indeed equally relevant to everyone else) with good common sense easy to follow advice on the legal implications of everything from pensions divorce and from the student grants you have available to what to consider when you make a will. I checked it out of the library (natch.) to assess if it was a good guide for teenagers, and I think the style is very accessible and authoritative though perhaps some might find the rather spare prose a little boring, I considered it rather authoritative. In any case, if you’re just trying to work out how to manage your budget if leaving home, where to live, what to think about if getting married and how to die, it’s a pretty decent guide.

27. Tyskerne på flugt (Germans on the move), John V. Jensen

A short but very informative book about the period of chaos after the second world war in Denmark. Our history stories maybe rightly tend to focus on all the “boy’s own” tales of derring-do under peril and invasion, but the period afterwards, when the gron-ups have to take over and sort out the whole mess, is perhaps more important. We have very many institutions set up in this aftermath that still survive and thrive today, thanks to that far-sightedness, while the mess in Afghanistan shows what happens when that sorting out isn’t prioritised.. Anyway, I picked this one up in our library, partly out of curiosity. One of my local running routes goes through an area of german graves, while a fellow parent once told me of the rather grim stories of our local school , when it was turned into an impromptu refugee camp. This book tells the real story – there were hundreds of thousands of people on the move away from an advancing Red Army who washed up in Denmark. Many of them old, sick or very young, and appalling levels of infant mortality shows how difficult conditions must have been in late 1944 and 1945. How the nation came to house, clothe, feed and educate them, and eventually, send them on their way, is an incredible story. A rather forgotten corner of history, there must have been many similar efforts in other European countries, it would be interesting to compare the experiences, especially in the light of current moral panics over rather fewer refugees fleeing war..

26. The Art of Travel, Alain de Botton

A thoughtful and interesting meditation on why we travel, what we do when we get there and why everything can feel a little flat when we get home. There is a lot to consider in here, including whether we should travel at all. It fit in nicely to our theme of the summer which was having a staycation rather than going somewhere. Some beautiful artworks and lots of historical context made it a natural partner to Rebecca Solnit’s Wanderlust which I also read this year. In fact I think Wanderlust is a better and more thoughtful book, but this is a very acces

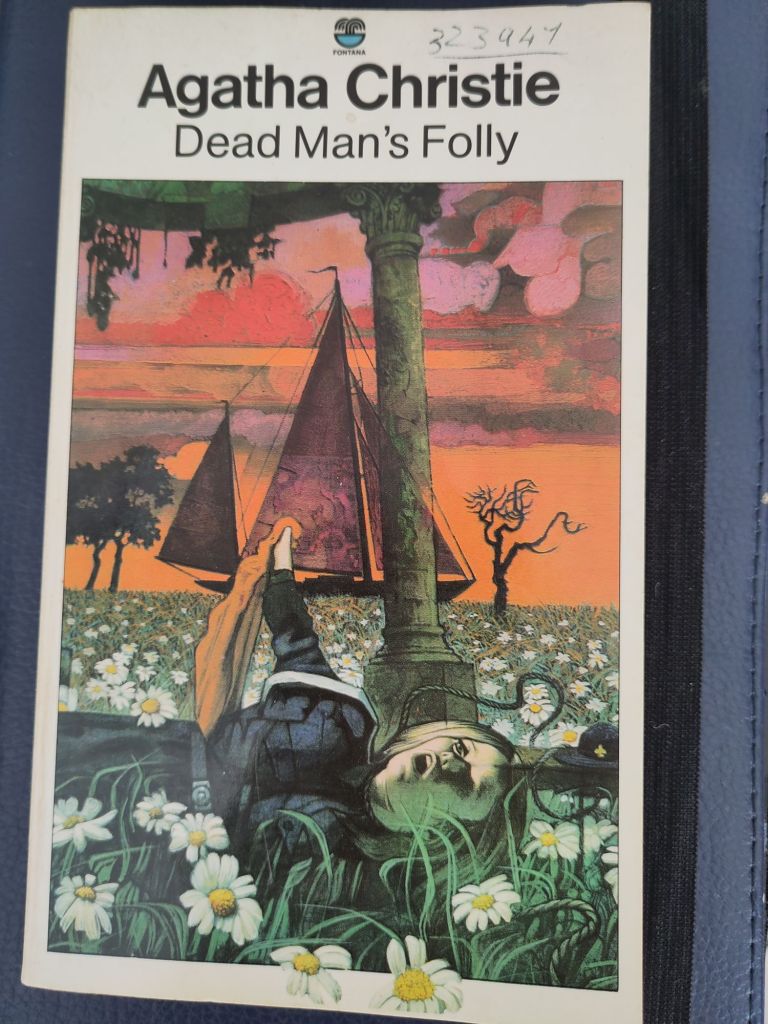

25. Dead Man’s Folly, Agatha Christie.

Pure comfort reading in a stressful week.

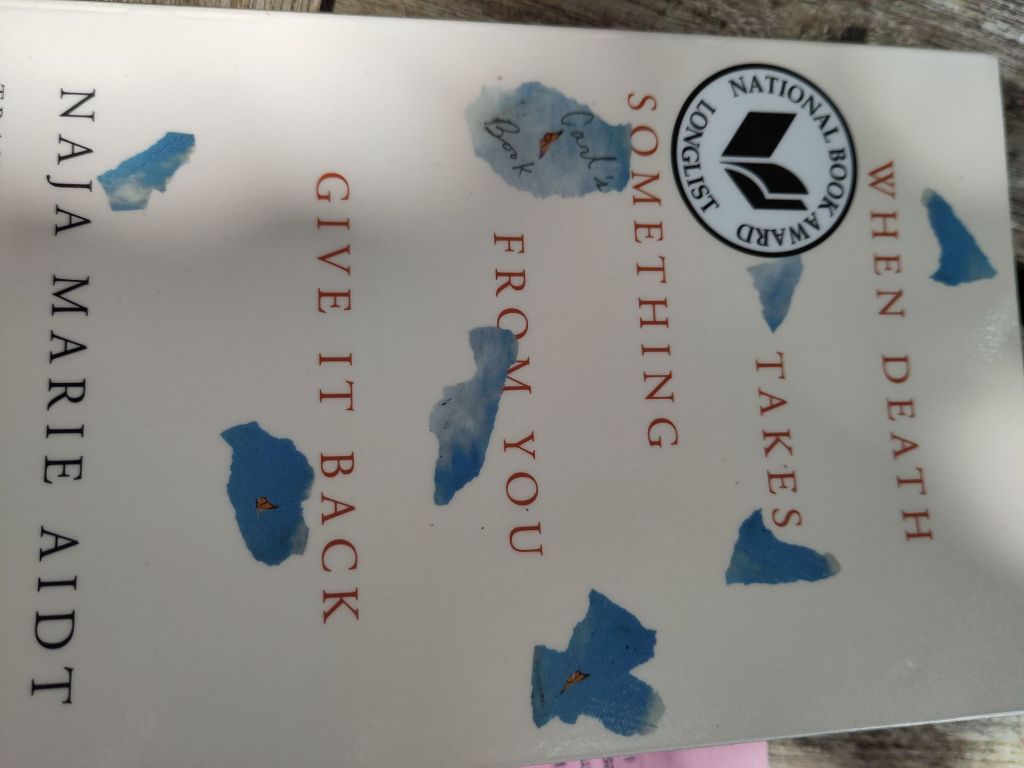

24. When death takes something from you, give it back, Carl’s book, Naja Marie Aidt

What can I say about this beautiful heartbreaker of a book. The grief and dislocation and ugliness of death and the devastation of those left behind is put in stark view. A book that is both a tribute to a special life but also an examination of grief. I can’t really describe it, I hope I will never come to understand it even more than I felt it today.

23. Vilje, Vabler, Neglelak (Will, blisters, nail varnish), Mette Foswald

22. Wanderlust, Rebecca Solnit

The chapter on hybrid warfare was fascinating. And quite scary. He describes very well how Russia was able to very cleverly take advantage of the fog of (hybrid) war (there’s Clausewitz again) and take over eastern Ukraine and Crimea before anyone in the West was at all clear on what was going on. I remember following the situation on twitter in 2014 and feeling utterly confused – it was clearly an invasion, or, was it? Later events have proved pretty definitively that it was an invasion and we should have been much more proactive in preparing and punishing Russia for it. Puck Nielsen doesn’t really talk about how the individual can learn from the Logic Of War, unless one happens to be a defence minister, general or other high level official of course, but to my mind, the most important lesson was from this chapter. We need to be prepared both physically in terms of individual and societal resilience, but also in terms of the information war. Those of us bruised by Brexit or engulfed by culture wars on social media can affirm all too well, how dangerous and difficult misinformation can be to deal with. We need to be much better at dealing with it. And on a societal level too. How do we inoculate our children who spend so much time in online worlds we barely use against this?

21. Difficult women, Helen Lewis

The culture wars have been so bad in the bad place, and Helen Lewis has been a bit of a controversial so I took this one in with a little trepidation and funnily enough found I needn’t had worried. It’s a thoughtful and beautifully written book on how women (mostly in the UK) managed to secure fundamental rights, but also the culture changes that have led to this point. It’s all scarily recent, and we should remember that as our sisters in the US are finding, it can always be turned back,. These kind of books are vital to keep the memory alive of the fight it was to get here. And it’s extremely entertaining too.

20. Pengekuren (The money cure), Mette Marie Davidsen.

I almost didn’t include this book as it is more of a practical how to guide than a novel or book read for fun. However, personal finance, particularly aimed at women seems to be having a bit of a moment, at least here in Denmark with the launch of several companies and initiatives like Female Invest, who have an explicitly feminist agenda to empower and inform women to take control of their finances and encourage them/us to invest and make wise financial decisions. I have some reservations about unbridled capitalism (who doesn’t?) but it’s undoubtedly true that money does very much equal power and if we want to push a sustainability agenda as well as one of equality, we need to have a seat at the table. This is very much a theme in the next book which I read concurrently with this one!

I picked this one up at my local library, and while it’s a bit old (published in 2008!) and some of the details are out of date it’s a very useful checklist of items to go through when doing some financial planning, which is really, as the.author makes clear, future planning.

My personal finances are more or less under control but I still find these books useful to go through, especially as big parts of the Danish tax and pensions systems are still rather unfamiliar to me. I wouldn’t necessarily recommend this one to a new beginner but I’m certainly going to see if there are more recent books by this author. She has a very good style, interwoven by personal anecdotes and illustrative examples.

19. The end of everything, Katie Mack

How will the universe end ? And what’s the point of anything if it does? Simultaneously simple questions and yet very big topics for a book. I enjoyed this one a lot. It’s both a really good summary of the field of cosmology at the present time (without equations!) and a suberbly witty and entertaining exploration of what it means to us as humanity to understand the fate of the universe. You may know Katie Mack from her consistently brilliant twitter account (maybe she has moved to another platform now?) and her quirky and funny outreach efforts really shine through here. It’s also a really good introduction to understanding working in modern science. A really good popular science book, though note, it will require some concentration to follow. It’s a linear narrative, so concepts build on each other and it’s quite dense with concepts

I will probably read it again to make sure I fully understand it, and it’s a mark of how gifted a writer Katie Mack is, that it doesn’t feel like hard work, but something I look forward to.

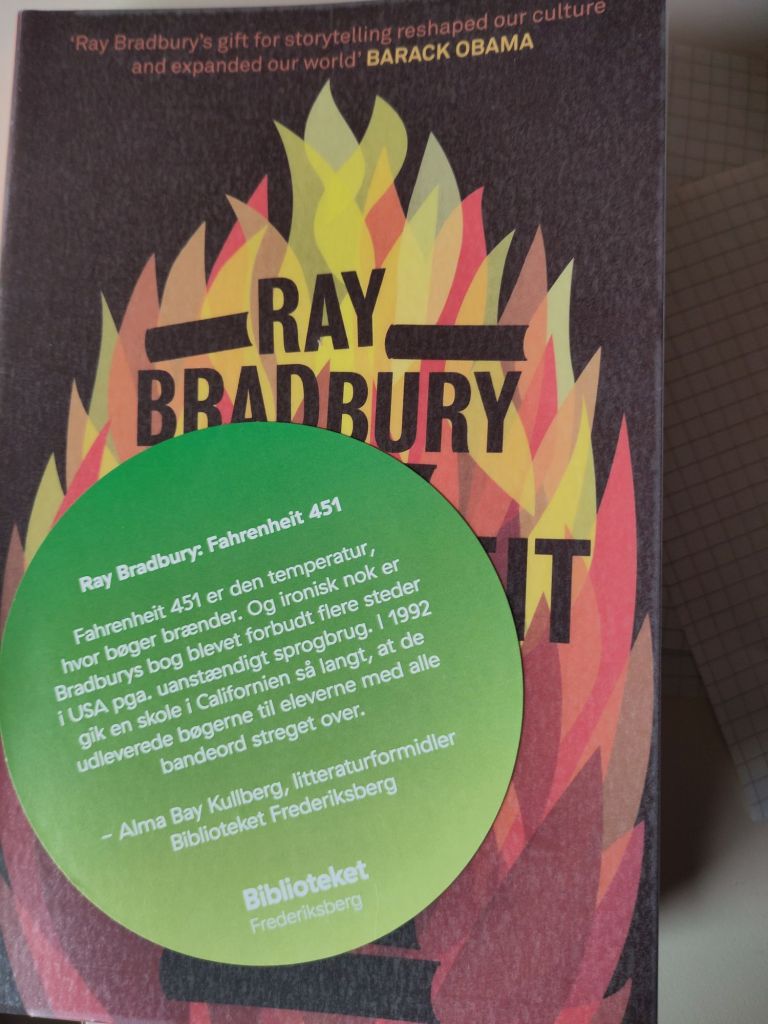

18. Fahrenheit 451, Ray Bradbury

Our local library has a “banned books” table right now showcasing classic books that have been banned in one jurisdiction or another (often, I’m sorry to say, US states). I remember seeing and picking up this book at my old school library several times but for some reason it didn’t appeal and I never read it at the time. I finished it off in 3 days this time! I thought it an ingenious look at the near future, though with a slightly dated 1940s twist that reminded me slightly of Brave New World. Even so, there are some disturbing similarities with our own times that seem prescient. In spite of the dystopian placing, there is a fundamental hope in the book, a belief that there are essential human sparks that will continue even in dark times. It has sparked more thought in me than I’d expected. I will certainly be passing this one on to the teenagers.

17. The Hobbit, J.R.R. Tolkien

Picked this up at a hotel. It’s the hobbit, you know the story… At least 30 years since I last read it and I’d forgotten most of it. Still a good story, even if Tolkien is a bit limited as a writer. Not a waste of time at any rate!

16. Humankind, Rutger Bregman

I picked this one up at the marvellous Bloom festival last year. I thoroughly enjoyed it, wonderfully written (and translated) with persuasive case studies. Even so, while reading it I could not help thinking over and over, “really”?, my inner scientific critic was working over time. It is genuinely hard to try and change what are pervasive assumptions about what motivates people, yet the author has done his homework and I came away wondering how to use these insights to be a better parent, scientist and manager at work, as well as a better person. I was brought up to try and think the best of all people, but a few years on the internet had left me rather jaded. Perhaps, now I’ve left twitter behind, this came at a timely receptive moment where it’s time to rejuvenate my faith in humanity and to act accordingly. Another recommendation to help make the world a better place.

15. Circe by Madeleine Miller

A wonderful book, I started just before bedtime thinking I’d just read a few pages and closed it finally at 3am. That kind of book.

The story is well rooted in Greek myth, but the figure of Circe allows a retelling of familiar stories from the female perspective: of the problems posed by immortality of the greek gods, Troy, Odysseus and his homecoming, Jason and his Argonauts and the minotaur. Extraordinarily well-written, this is yet another boon I’d never have read if it hadn’t been for the marvellous librarians of Frederiksberg. Astoundingly good

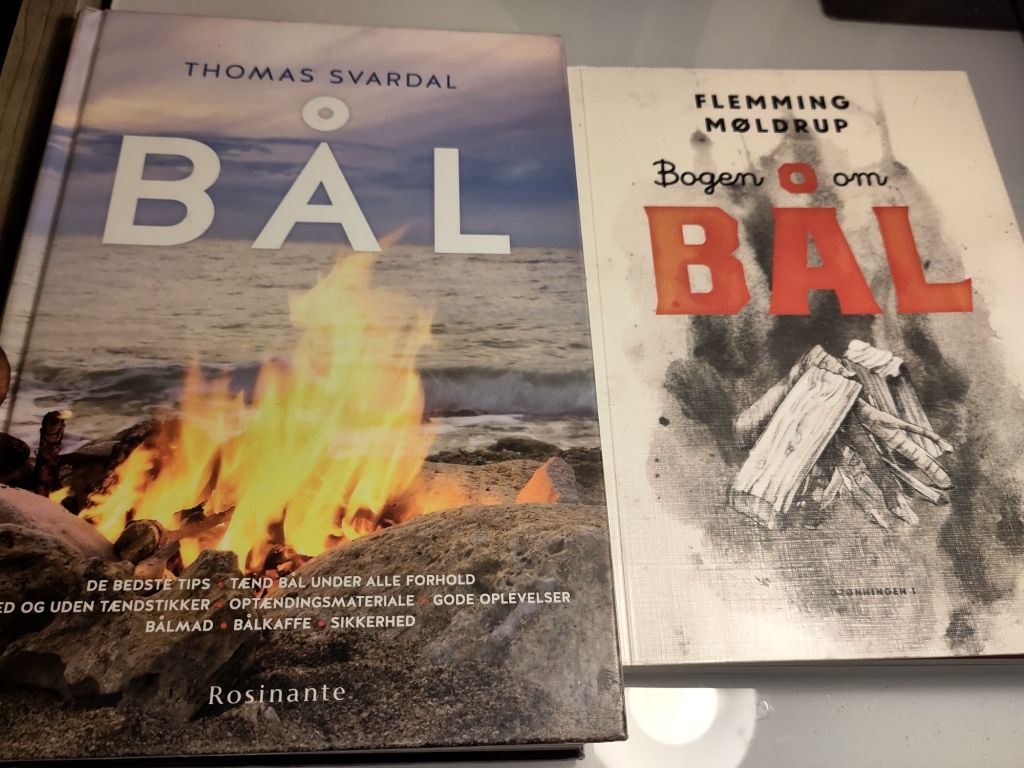

14. Two books about building bonfires: Bogen om bål (The book about bonfires) by Flemming Møldrup and Bål (bonfire) by Thomas Svardal

Book number 14 is actually 2 short books. I’ve grouped them together because they are on the same subject, both beautifully illustrated, and yet quite complementary. Sitting around a camp fire in the open air must have been once one of the most common human experiences, but it’s probably one our urban world is, (or maybe was ?) starting to miss out on. In the friluftsliv culture of Denmark and I suspect more widely, across the Nordic countries, having a little bonfire to make fresh coffee or bake twist bread over is an extremely common activity. Often a normal part of going for a walk, whether hiking in the Norwegian mountains or walking in the Danish beech woods. These 2 books both touch on the philosophy of having a bonfire as well as the practicalities of building and lighting fires.

Thomas Svardal’s gorgeous photographic exploration (translated from Norwegian ) is very much focused on the techniques, different ways to construct, the differences between types of wood, which is better in the soaking rain, which in the snow, how to light them, and has some fascinating input from Sami traditions. It’s the kind of almost lost knowledge that makes you realise just how skilled our ancestors must have been to survive in difficult conditions. He encourages the reader to try out different methods of lighting a fire and provides an expert tick list of techniques to go through. There is also good advice on helping children to discover the arts of enjoying a good fire.

Flemming Møldrup offers also some good practical information but his book, also beautifully illustrated with pencil and watercolour sketches offers both history of fire, and puts the human relationship with it in perspective. His narrative is also a personal philosophical discussion on the importance of going out into nature to rediscover that we’re part of it too. It’s a satisfying book, particularly for anyone who has ever struggled to light a fire. His philosophy is almost one of mindfulness – it’s hard to light even a small fire in the forest without concentrating on it, planning properly and doing everything in the right order. The book is structured around the whole process, from gathering the wood, making the tinder, generating the sparks, building the fire to making sure it is completely out, clearing up the fire site and leaving the place clean and tidy.

Both books skate a little lightly over the environmental impact if everyone in the world suddenly started burning wood (this would not be good!), though Flemming Møldrup argues convincingly like John Muir, that leaving the towns to get closer to nature is essential if we should learn to protect it and learning to make fire is part of what makes that experience so special. Having a campfire in the forest is in the end a luxury of time, resources and access. In Denmark (and across the Nordic region) we’re lucky to have access to a huge network of shelters and camp fireplaces, as well as plentiful wood to burn. These are both good and complementary guides as to why and how to make the most of those resources. Both books have much to recommend them and are guaranteed to have you outside making coffee over an open fire at the first opportunity.

13..The Mighty Dead: why Homer Matters: Adam Nicolson

I can’t really make my mind up about Adam Nicolson.

He’s a journalist by trade, but from a wealthy upper class family with a background in Eton, Oxford and all the rest. I’ve read 2 of his other books, about the Shiant Isles and about the ocean, both of which occasionally had moments of brilliance but also moments that had me wondering if what I was reading was actually accurate or just plausible bullshit. Perhaps exposure to Boris as Prime Minister has simply made me allergic to the Ancient Greek obsessed upper classes? (The 5th Baron Carnock, for it is he, does at least produce better prose than a large language model).

His full canon of books are on a surprisingly broad range of topics, none of which he seems to have an officially acknowledged expertise in, but which seem in general to be well researched. I think my difficulty is that he blends scholarly insights (rarely his own given the extensive footnotes) with wild guesses and suppositions and it’s not always clear where one ends and the other starts.

The overall effect is rather like one of those late evenings as an undergrad at university with perhaps too many bottles of wine open on the table where the world seems to fall marvellously and significantly into place, but the next morning you’re left trying to work out exactly what was said that was so significant and if any of it was half as profound as you thought it was?

My local library apparently has had a theme on the Iliad and I picked up this latest book about Homer’s works from that table – I’m glad I read it and I did enjoy it. But it didn’t particularly make me want to read either the Iliad or the Odyssey again..

Which is really a pity because I think there are some really interesting insights in the book about Homer, even if there are also a few wild geese chased and there is a glorying in the violence and especially sexual violence of Homer that is frankly disturbing. On the other hand perhaps that’s just the source material? I think the insights into the Iliad as a clash of nomadic steppe people versus civilised cities of the Mediterranean interesting as an idea, but I wonder if there is really much evidence for this? Likewise his suggestion of a much earlier provenance than typically assumed. Much of the Odyssey is skimmed over but the section on Odysseus’ journey to Hades being actually located in Spain seems more than a little far-fetched. But again, I don’t know, it’s not my field and that’s the problem, he seems too certain and brings in too many outside lines of evidence that seem a bit thin.

Nonetheless it’s an interesting book and a really good guide to interpreting the way Homer is written down, with the linguistic overtones particularly well brought out. The writing is often beautifully lyrical, with real skill in incorporating the lines of Homer within the narrative of the book without it feeling clumsy. However, he rarely uses a sentence when a paragraph will do. Even more editing would help. I get it though – this has clearly been a labour of many years of research and the author clearly didn’t want any of it to go to waste. The effect is slightly like reading a PhD thesis though, rather than a more popular work.

I’m not quite convinced Homer “matters” on the basis of the book, but there are still some startling parallels with Europe’s current moment where peaceful civil society is again threatened by gangsters motivated largely by plunder and some twisted notion of “honour” (which doesn’t include respecting women, children or indeed civilians or the rules of war). It’s probably a good introduction to Homer and to the history of the studies of Homer, though be warned there are some graphic descriptions of violence and sexual violence in the book.

12. Till Topps I Norges Nasjonalparker: Gjermund Nordskar

It’s a fun book, not exactly a candidate for a Nobel prize qua writing style, but it actually also functions as a good taster guide to the 37 (in 2014) national parks of Norway. The author Gjermund has that appealing enthusiastic can-do attitude of the young that makes me want to dig out the skis and rucksack straight away. I’ve made several mental notes of places I’d like to visit in the future and I suspect this will be on my “planning mountain trips” shelf for a good long while.

Appropriately for a book about Norwegian national parks, I finished this while on holiday in the Norwegian mountains.. As it’s written in Norwegian bokmål I can understand it reasonably well and the back story of a sudden illness, disrupting a long-planned gap year is simple enough. The author recovers sufficiently, after 6 months of rehabilitation, to decide to use the remainder of his gap year ascending the highest point of every Norwegian national park. It’s a fairly gruelling undertaking given they decide to do it in one go and as far as possible on skis. Some of the peaks are pretty straightforward, others require 3 goes to get the weather conditions sufficiently calm for the ascent, or the assistance of a friendly snowmobile driver or even semi-professional climber. The final two peaks involve sea kayaking..

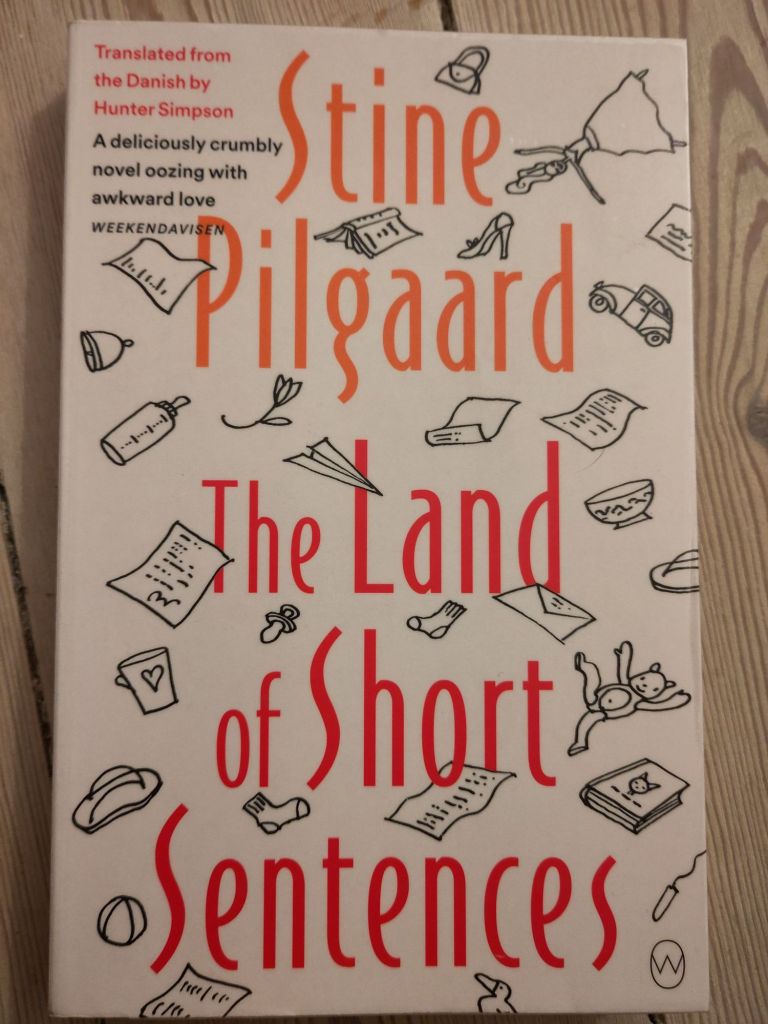

11. The land of short sentences: Stine Pilgaard

I loved this book. It’s hard to explain why but it’s just a perfectly crafted piece of warmth and beauty that somehow manages to be warm without being sentimental, funny without being condescending and awkward and strange and absurd without ever leaving contact with reality. It’s a great introduction to the højskole movement and almost made me want to move to Jutland, without being a pæon to an imagined place. In the form of little vignettes, through the course of a year with an unusual narrator, an oracle of the problem pages, it’s an easy one to pick up and enjoy when you can fit it in. And as for plot, there kind of isn’t really one, other than the normal life we all live through, yet nevertheless there is a tender development of character through the academic year at an ordinary high school. The travails of parenthood are particularly brilliantly presented. There are also some hilarious scenes featuring Anders Aggers, a kind of danish Louis Theroux..

Really, just put this book on your reading list. It’s wonderful. (It’s actually a danish book but I read it in the English translation, I didn’t realise that at the time I picked it up from a library table in my kommune’s main library. Yet again, Frederiksberg librarians are demonstrating their worth as “kulturformidler” – cultural providers (?)).

If you are Danish, you’ll probably find the fun højskole sangbog occasional songs extremely amusing too.

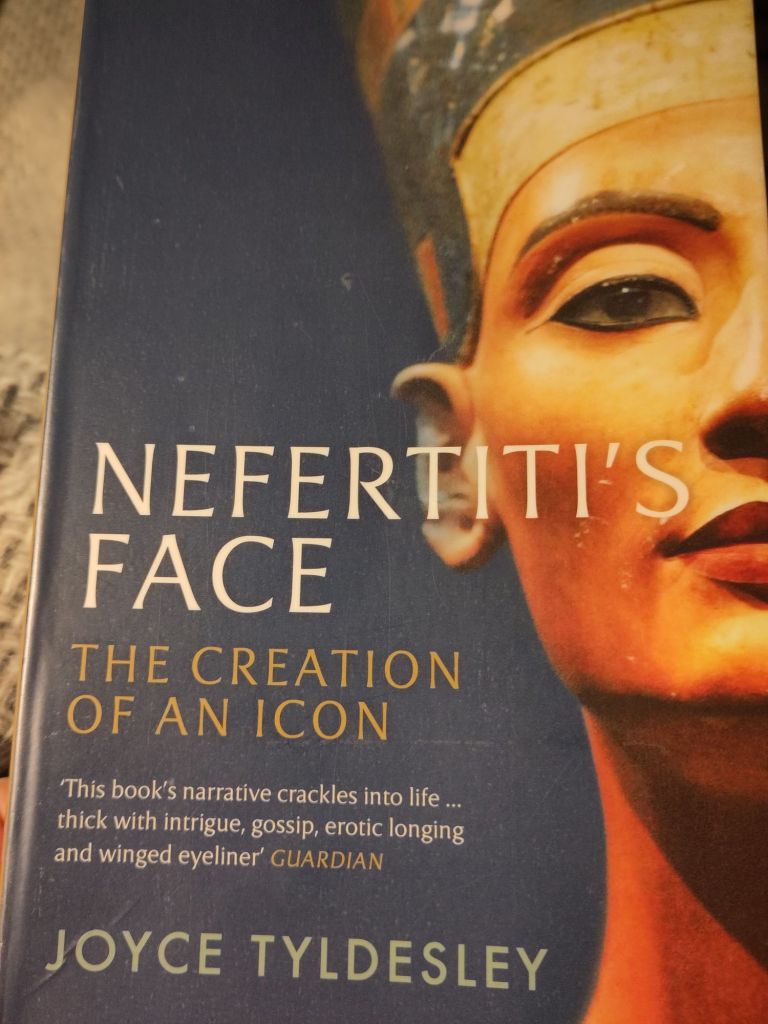

10. Nefertiti’s Face: The creation of an icon: Joyce Tyldesley

A slightly curious book about the beauty that is the famous Nefertiti bust, currently residing in the Neues Museum in Berlin. The book does a good job describing the history of the finding of the bust, and some interesting background on Akhenaten and Amarna. Mostly what I’ve taken away from it though is how speculative so much of Egyptology actually is! A lot of what we “know” about Egyptian history turns out to be guesses, supposition and based on pretty weak evidence. It is in any case an interesting diversion and a welcome antidote to some of the wilder speculations on the History channel and it’s ilk …

9. Wild From Lost to Found on the Pacific Crest Trail: Cheryl Strayed

A compelling book that once I’d started I didn’t want to put down, and yet it felt a bit like it ran out of energy before the end. It’s the story of a woman going through a breakdown.

8. Krigens Logik (the Logic of War): Anders Puck Nielsen

It seems a hideous concept that war can have a logic, but after reading this book I find it strangely comforting to think that we can at least partly explain how and to some extent why wars are fought.

I’m interested in history, but I’ve never read Clausewitz’s On War, or indeed going further back Sun Tzu’s The Art of War, but the former at least is quoted several times in this book. Anders Puck Nielsen is an analyst in the Danish military academy and has clearly done his research. I particularly liked that each chapter starts with an actual wartime incident,which he then uses to illustrate a particular point of the logic of war.

We are, as he also points out, mercifully unused to wars of aggression in western Europe after decades of peace, which probably explains why so many of us have found the Ukraine invasion (since 2022, though the original invasion in 2014 is also discussed in some helpful detail) so disturbing.

The events since the invasion of Ukraine in 2022 has torn up all our assumptions about how the world works. That “Peace Dividend” in western Europe is looking more than a little shaky. (I acknowledge by the way that this is not true if you live in many other parts of the world, as does Puck Nielsen). He rightly points out too that only by having politicians and militaries that understand the logic of war can we defend ourselves, as well as seeking to find ways to understand our opponents. This is really the point of the last chapter on atomic weapons- putting ourselves in their position to work out how they will react is surprisingly difficult, but absolutely essential if we’re to avoid nuclear oblivion in the coming century.

Other chapters on new technology and especially drones and cyber warfare are particularly relevant, not having been around when Clausewitz was writing. They bring a new calculation to how governments need to prioritise and plan their defence strategies that is not as immediately apparent as I’d thought.

Other concrete examples from the Korean war, Libya and the Tanker war in the Persian Gulf in the 1980s were also really illuminating, explaining clearly how events that happened before I was born, or that I only vaguely recall, played out. And more importantly Why they occurred as they did.

The chapter on hybrid warfare was fascinating. And quite scary. He describes very well how Russia was able to very cleverly take advantage of the fog of (hybrid) war (there’s Clausewitz again) and take over eastern Ukraine and Crimea before anyone in the West was at all clear on what was going on. I remember following the situation on twitter in 2014 and feeling utterly confused – it was clearly an invasion, or, was it? Later events have proved pretty definitively that it was an invasion and we should have been much more proactive in preparing and punishing Russia for it. Puck Nielsen doesn’t really talk about how the individual can learn from the Logic Of War, unless one happens to be a defence minister, general or other high level official of course, but to my mind, the most important lesson was from this chapter. We need to be prepared both physically in terms of individual and societal resilience, but also in terms of the information war. Those of us bruised by Brexit or engulfed by culture wars on social media can affirm all too well, how dangerous and difficult misinformation can be to deal with. We need to be much better at dealing with it. And on a societal level too. How do we inoculate our children who spend so much time in online worlds we barely use against this?

This is perhaps not the most relaxing book to read, but I firmly believe that knowledge and understanding is empowering. If we understand how wars work, we can start to see how we can defend ourselves against it. Like, I suspect many, though perhaps not enough people in Europe, I fear we have lived too long in a fool’s paradise, ignoring what was happening beyond our borders. It’s time to account for that. At the very least, readers will come away understanding that the war in Ukraine is indeed one that should concern us all.

This is one of those books that you read and wish was translated into English (and other languages) so you can pass it around your non-Danish friends. In the immediate absence of a translation, I can only recommend you check out Anders Puck Nielsen’s channel on YouTube, where some of the same principles are reflected in his extremely informative videos (in English). The book however is a really comprehensive overview that tackles many of the fundamentals so I hope it will one day also be accessible outside the Scandinavian countries.

Please make it so publishers!

7. Gå-bogen (the walking book): Professor Bente Klarlund Pedersen

Another find from my lovely library – definitely not the kind of book I would normally go for, its beautifully presented with lots of charming Danish photos – perfect for the Instagram influencers generation was my first thought. However. I recognised the woman on the cover as an eminent Danish researcher in especially lifestyle diseases like diabetes. Not just the usual fluff exhorting us to eat less and move more then? Flicking through it quickly I detected a much higher than usual concentration of actual science in the book so dropped it into my bag when I checked out..

The book is indeed an exhortation to exercise – but more specifically to simply walk more. She blends it very nicely though: research on all sorts of lifestyle influenced diseases like heart disease and cancer, with philosophical, spiritual and cultural meditations on the meaning and transformation that just walking can and can’t do. She ends with a particularly identifiable chapter (to me at least) about how exercise and walking shouldn’t necessarily be an end in itself, that walking is good for the soul and forces us to take time out.

Overall a very thoughtful and informative book and considerably more in depth than I’d expected when I picked it. Another win for the Frederiksberg librarians.

(As an aside, the author thanks her 4 children + 9 grandchildren in the acknowledgements. As always when reading these kind of things I can’t help wondering how rare that must be in other countries: a woman professor who has 4 children and an eminent career? I occasionally think that I’d either not be a scientist or not have kids if I’d remained in the UK. That may not be entirely true, but role models like Prof. Klarlund are important and she’s far from the only one I know of here. The social democratic principles of Denmark have clearly been getting some things right.)

6. Broderier (Embroideries): Marjane Satrapi

Very funny, poignant and tragic but most of all utterly realistic. I can absolutely imagine this marvellous group of women chatting around the tea pot after a big family meal. There is a true element of the sisterhood, whatever that means here, that the state sanctioned suppression of women’s rights seems to sharpen into this biting satire. These women have sometimes terrible choices forced on them and awful things happen but they still manage to support and laugh at and with each other. I’ve been a huge fan of Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis. This is a short book, which I finished in less than half an hour, but I’m adding it here too because graphic novels for adults have been a huge discovery for me – I don’t think they were very widespread when I was a kid, but I really enjoy the experience of reading them.

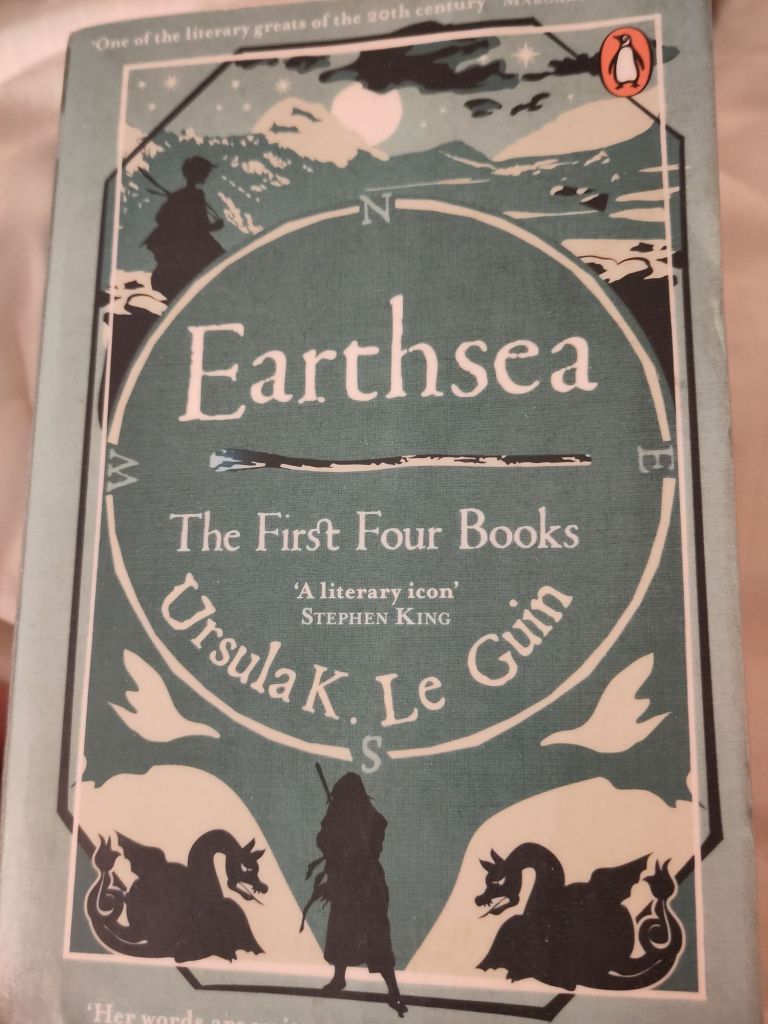

5. Earthsea: Ursula K. Le Guin

I’m almost tempted to count this as 4 books, which is how it was originally published, but let’s just say I was so gripped by the first book I read the whole volume of 4 books almost in one go – staying up far too late a couple of nights to demolish it in basically 3 sittings. And what a book it is.

If you haven’t read it, you really must. It’s beautifully lyrical, a fantasy novel that deserv s to be considered great literature for the quality of the writing alone… It also has wonderful empathetic characters and some knife edge plotting, plus a streak of something that is politically aware but always very light of touch, but nonetheless there. A rare gift to make you examine your own assumptions and prejudices without it feeling intrusive. The settings are so beautifully described and there is real development of character and plotting through the books.

I had originally thought I’d re-read Lord of the Rings after watching the films (again), so glad I spotted this in our wonderful library where a sympathetic librarian had laid out a full table of Ursula Le Guin’s works.

An absolute treasure, I only wish I’d discovered her writings earlier. It’s the kind of book that I can’t wait to discuss with my family and friends. So beware. If you’re visiting my home you may find a copy pressed into your hand with an urgent entreaty to read it…

4. Parable of the sower: Octavia E. Butler

I hadn’t expected to be updating this page so soon. I settled down with a new book at around 9pm and for the first time in a very long time read it in one sitting. Which I suppose tells you something about how gripping this book is. It’s again one I wouldn’t have chosen except for its prominent position in a stack on one of my local library’s themed tables. The librarians are really on top of their game right now.

I confess to finding dystopian novels generally a bit unconvincing, they tend to think the worse of people and I am generally a little more optimistic than that. Possibly that is my white middle class European privilege shining through. Especially the latter part of this novel suffers a little from horrific but somewhat unconvincing societal breakdown. But then, we could look at several countries (Venezuela anyone? Lebanon, parts of Mexico perhaps) and give them as counter examples so perhaps I had better not be too comfortable. Some elements I find terrifyingly convincing, the slow degradation of a society and services and decay that no one notices, the changing climate that acts as a stressor and threat multiplier. And we don’t have to look far to find some scary parallels, the Jungle in Calais, the rolling back of worker’s rights and the near slavery conditions of modern agriculture in at least some states and countries, police brutality and the privatisation of essential services like fire fighting, the opioid and spice epidemics. Other more positive parts are convincing too: neighbours and friends banding together happens much more often than not, solidarity, reciprocity are invariably part of the response to natural disasters. The idea of growing as healing, that education is important and literature and poetry can free us. The idea of earthseed is compelling.

Other elements of this book are extremely creative and even optimistic: the sharing, the idea that in 2024 we’d have astronauts on Mars and a joint base on the Moon is however sadly further out of reach than it must have seemed in the early 1990s when the book was written.

Altogether, a really excellent book and a huge recommendation for near future Dystopia with an optimistic angle that the horror and violence doesn’t manage to overwhelm. I will have to read the next volume in the series now, and I’m a little surprised as it’s not the kind of novel I’d normally read.

So, all in all, bravo the brilliant Frederiksberg librarians…

3. Maus: Art Spiegelman

There are books that haunt you forever and there are books that after you’ve finished them you want to sit quietly in a blank room and think back over what you’ve just read. Maus, which I picked up at our local library while on the hunt for something else, is a graphic novel and, like Persepolis (which it predates), it fits in both categories.

I’d started it once at a friend’s house but never finished it and when I spotted it again I remembered that it has recently been banned in some US schools, which seemed like a good reason to start reading it again.

It’s a poignant and often quite funny book given that it’s about one family during the holocaust. The transmuting of the characters into animals makes the horror bearable. I found it very compelling and after a certain point read on and on, it was difficult to put down.

I wouldn’t necessarily take it to the beach, as especially at first it needs some concentration, but it’s a book everyone should read and digest. I can’t really say more than that. It’s actually perfect.

2. Bonnie Garmus: Lessons in Chemistry

I hadn’t expected to be posting so soon but I stayed up far too late in order to finish this book… It was a gift and not one I’d have necessarily chosen myself, but once I’d entered into the weird, wonderful and difficult world of Elizabeth Zott, a fiercely independent chemist and single mother in the early 1960s, I couldn’t put it down. It was hugely enjoyable but also rather thought-provoking. The sheer viciousness of the cage put around white middle class women who want to work and have their own lives in that time should be enough to counter the 1950s nostalgia that seems a little too prevalent for my liking. The main characters are spiky but very likable, if not always very believable.

There are some of the usual plot and character clichés in this kind of book that I find a little disappointing, and a Deus ex machina towards the end brings it all a little too neatly together but it is an entertaining and thoughtful novel, with a strong but not overpowering feminist message, and a clear theme on the importance of being an ally. This makes it all sound far too worthy.. It’s actually a really fun book and I’ll be passing it on to my younger teenage female relatives as I’m sure they’ll also enjoy it.

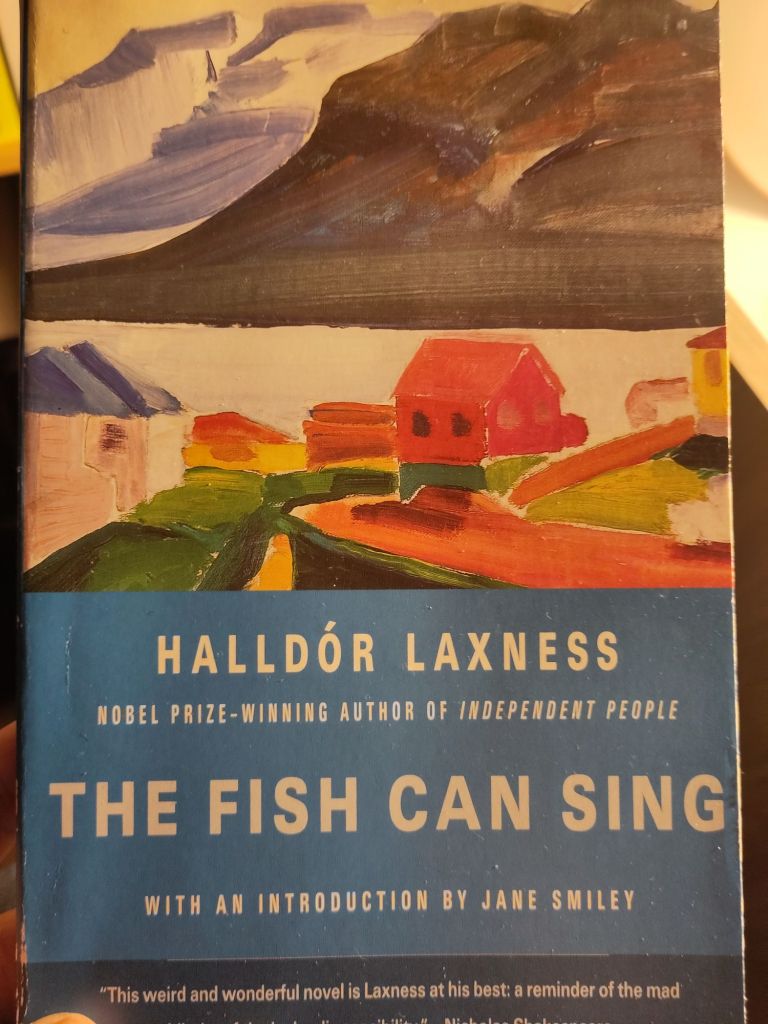

1. Halldór Laxness: The fish can sing

My first book of 2024.. I read Laxness’ Nobel prize-winning “Independent People” years ago when I was a PhD student in Iceland. This makes me want to read it again. I feel my tastes have matured. I got a lot out of this book. It’s very comical, absurd and funny but also rather poignant, dark and Laxness certainly doesn’t take prisoners. He revels in puncturing the self-important as well as those captured by nostalgia. I remember praising independent people to an Icelandic scientist, years ago. She told me that he was not always popular in Iceland because he wrote about times, places and actions that people would rather forget. Or perhaps look back on and mythologise. I definitely can see that in this book. But both this and the aforementioned Nobel prize winner are really great context for considering Iceland and how it became the land it is. And some of the themes are scarily up to date. It’s really a brilliant piece of writing, Iceland’s George Orwell, in many ways, if Orwell had managed to develop an absurd sense of humour.

The protagonist is the young Álfgrímur, an adopted young boy growing up in idyllic but humble circumstances in Reykjavík who becomes interested in his (almost) kinsman, renowned Icelandic singer Garðar Holm. But the plot of the story is very much by the by. The beauty of this book is in the characters, the atmosphere and the language. The translation by Magnus Magnusson is marvellous.

• • •