Category: Nature

Sea Ice loss in Antarctica: Sign of a tipping point?

The Danish online popular science magazine is currently running a series on tipping points in the Earth system with a series of interviews with different scientists. They asked me to comment on the extraordinary low sea ice in Antarctica this year. You can read the original on their site here. But I thought it might be interesting for others to read in English the piece which is a pretty fair reflection of my thinking. So I’m experimenting a little with DeepL machine translation which I consider much more reliable that google’s competitor. I have not edited anything in the below!

I have been promising a piece on West Antarctica for a while – which I’m still working on, but hopefully this is interestign to read to be going on with!

A sudden and surprising loss of sea ice in Antarctica could be a sign that we are approaching something critical that we need to prepare for, warns an ice researcher from DMI.

The climate seems to be changing before our eyes.

2023 has seen record high temperatures both on land and in the ocean, which you can read more about in the article ‘Is the climate running out of control like in ‘The Day After Tomorrow’?

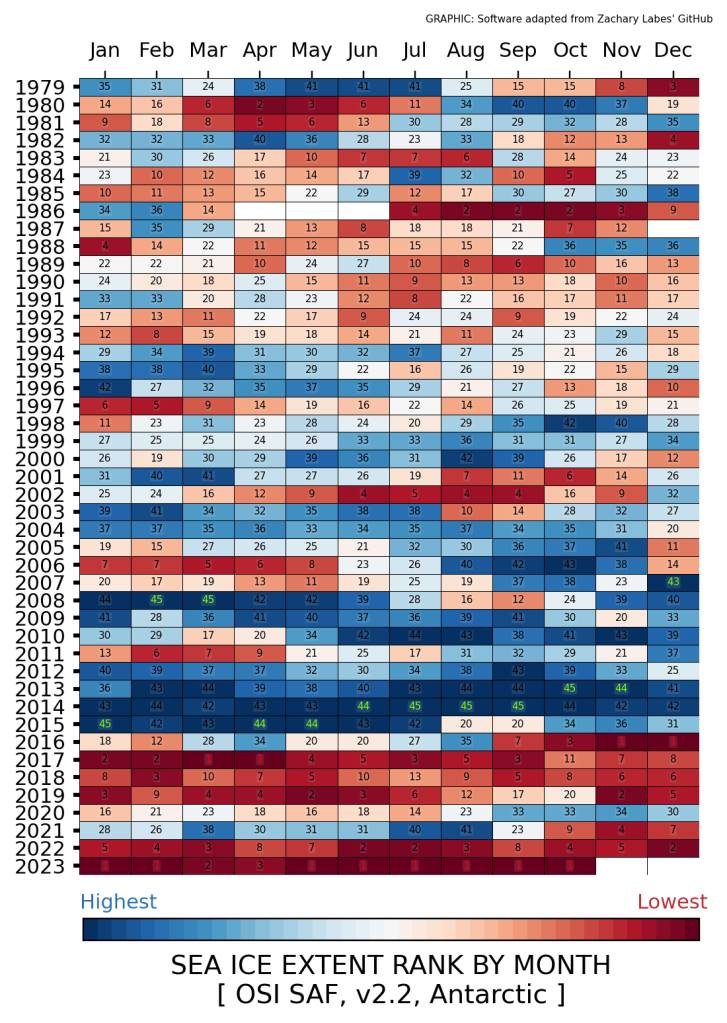

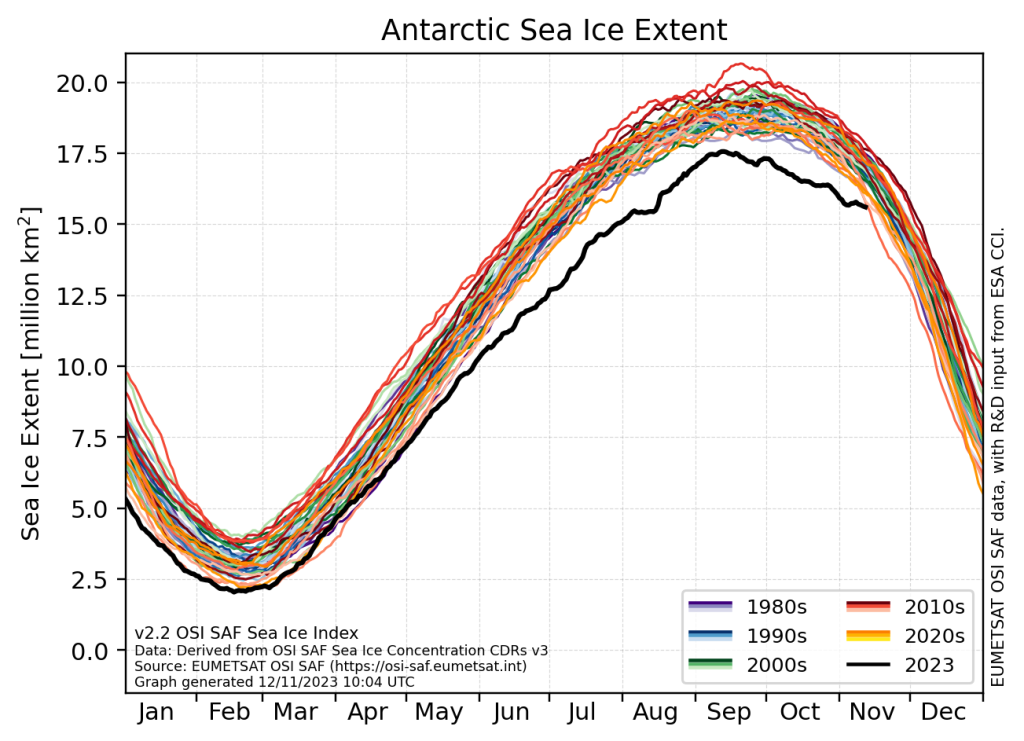

In Antarctica, there has been a sudden, violent and in many ways unexplained lack of sea ice, which normally melts in the summer and re-forms in the winter.

Since then, some of what was lost has been recovered, but when the sea ice peaked in September 2023, 1.75 million square kilometres of sea ice was still missing. This is equivalent to about 40 times the area of Denmark.

This is by far the lowest amount of sea ice ever measured in Antarctica.

“The melting sea ice in Antarctica is not unexpected in itself, because we have long predicted that it would disappear due to global warming,” Ruth Mottram, senior climate researcher and glaciologist at the Danish Meteorological Institute (DMI) tells Videnskab.dk.

The climate seems to be changing before our eyes.

2023 has seen record high temperatures both on land and in the sea, which you can read more about in the article ‘Is the climate running out of control like in ‘The Day After Tomorrow’?

“But to suddenly have a very, very large disappearance like that is a big surprise. We can’t explain why it happened, and our models can’t recreate it either,” she says, but adds that over time, the models are getting closer to reality.

Disturbances in the Earth’s system are probably connected

Videnskab.dk has in a series asked five leading Danish scientists to assess the state of the climate from their chair – in this article Ruth Mottram.

Ruth Mottram is head of the European research project OCEAN:ICE.

The OCEAN:ICE project

The researchers in OCEAN:ICE, led by Ruth Mottram as principal investigator, will take measurements below the ocean surface. This will provide more knowledge about the temperatures in the ocean around Antarctica.

They will also calculate how fast the ice is melting in Antarctica due to ocean processes and warming in the air. They will also investigate what the lack of sea ice means for the rest of the Antarctic system.

Ruth Mottram cites as examples:How does it affect ecosystems? For example, many animals feed on the small crustacean krill, whose life is affected by sea ice. Will more waves now reach the Antarctic ice sheet and perhaps lead to more icebergs and more melting? Will glaciers and icebergs become more sensitive to heat? Or, on the contrary, will less sea ice trigger more snow over the continent, which could even stabilise the glaciers?

More specifically, researchers will focus their efforts on seven areas, which you can read more about on the OCEAN:ICE website.

In the project, researchers will, among other things, take measurements under the sea surface in Antarctica to gain more knowledge about how the ocean and ice interact.

Is melting sea ice linked to warm water in the Atlantic?

In the North Atlantic, sea surface temperatures in some places have been as much as five degrees above normal.

To an outsider, it seems obvious that this could have something to do with melting sea ice.

However, according to Ruth Mottram, the two factors are not necessarily directly related. Sea ice in Antarctica melts from below. Therefore, the temperature at the bottom of the sea is far more important than the temperature at the surface.

“But if there’s one thing I’ve learnt over the past 15 years working at DMI, it’s how interconnected the whole world is. So I think we’re seeing some disturbances throughout the Earth system that are unlikely to be completely independent of each other,” she says to Videnskab.dk.

Ocean Professor Katherine Richardson made the same point earlier in the series. You can read about it in the article ‘Professor: The oceans are warming much faster than expected’.

Lack of knowledge and observations

Ruth Mottram emphasises that far more observations from Antarctica are needed before we can say anything definite about the causes of the rapidly shrinking sea ice, but: “It could indicate that the Antarctic sea ice has a critical tipping point like the Arctic, where for a number of years we see a slow decline year by year, and then suddenly it drops to a new stability where it is very low compared to before.””But we don’t know, because there are parts of the system that we don’t understand and that we haven’t observed yet,” explains Ruth Mottram.

Possible reasons why sea ice is disappearing

Ruth Mottram talks a lot with international colleagues about why the sea ice is currently experiencing a significant decline.

She explains that there are different theories, for example that warmer water from below is coming into contact with the sea ice and melting it from below, and that warmer air may be feeding in from above.

In Antarctica, the direction and strength of the wind has a big impact on the state of the ice (click here for a scientist’s timelapse of how Antarctic weather changes rapidly).

Perhaps the sea ice has been hit by “a very unfortunate event”, where it is both being hit by warm water from below and being affected by weaker winds from changing directions, which is holding back the recovery of sea ice.

Again, more research is needed.

Melting ice also contributes to sea level rise, and the Earth is actually designed so that melting in Antarctica hits the northern hemisphere much harder than melting in Greenland. So, bad news for the ice in Antarctica is bad news for Denmark.

Even more bad news is on the horizon.

The natural weather phenomenon El Niño looks set to get really strong over the next few months. A so-called Super-El Niño will likely only make the world’s oceans even warmer.

“We know that the ocean is going to be really, really important in the future in terms of how fast the Antarctic ice is melting and what that will mean for sea level rise,” says Ruth Mottram.

We can’t just wish the world would look different

The climate scientist does not fear huge increases or a violent change in climate overnight, as depicted in the 2004 disaster film ‘The Day After Tomorrow’. She points out that even abrupt shifts in the Earth’s past climate have occurred over decades or centuries, not a few months or years. Still, Ruth Mottram thinks it makes sense to start talking a little more openly about how we tackle severe sea level rise – which on a smaller scale can still be sudden – and large-scale climate change.

The Antarctic ice sheet is the largest on the planet

The Antarctic ice sheet contains around 30 million cubic kilometres of ice. This means that around 90 per cent of all fresh water on Earth is frozen in Antarctica.

If all the ice sheet in Antarctica melts, the world’s oceans will rise by around 60 metres. Even if we stay within the framework of the Paris Agreement, we risk that melting Antarctic ice from Antarctica will cause sea levels to rise by 2.5 metres.

Ruth Mottram notes that the more we exceed the limits of the Paris Agreement, the faster sea levels rise – and slower if we act quickly and stay close to the set limits of preferably 1.5 and maximum 2 degrees of temperature rise compared to the 1800s.

“The Earth’s climate system may be shifting towards a new equilibrium, which could result in a different world than we have grown up with,” continues Ruth Mottram.

“It is already affecting us and will do so increasingly in the future. That doesn’t mean it will be a total disaster, but we will probably get to the point where we have to adjust our lifestyles and societies.”

“It won’t necessarily be simple or easy to do so, but we can’t just wish for the world to be different than it is,” says Ruth Mottram.

In another article in Videnskab.dk’s climate series, Professor Jens Hesselbjerg Christensen notes that the world’s finance ministers – including Denmark’s – must pull themselves together and find money to slow climate change by, among other things, putting a cap on greenhouse gas emissions.

“We are in the process of allowing future generations to accept that large areas of land will become uninhabitable because the water level rises too much,” he says.

‘Bipolar’ researcher: Keep an eye on Greenland too

In the short term, Ruth Mottram is interested in finding out what the consequences of El Niño will be and how Antarctica will change over the next few years.

But she also has her sights set on Greenland.

“Because there have been so many weather events elsewhere, it has gone a bit unnoticed that we’ve had a really high melt season in Greenland this year.

“It can give us the opportunity to see very concretely how weather and climate are connected. That’s why the next few years will be really interesting in Greenland,” says Ruth Mottram, who has also conducted research in the Arctic for many years.

The next article in Videnskab.dk’s series on the state of the climate will focus on Greenland.

Musings in summer 2023: impacts + adaptation

I was talking to some friends today about climate change – in the light of the latest #AMOC paper, suggesting a tipping point. I’m far from an expert on AMOC so if you’re here for that I suggest this comprehensive piece on real climate from Stefan Rahmstorf.

Or the TL;Dr version in thread form compiled by Eleanor Frajka-Williams, PI of OCEAN:ICE sister project EPOC.

Anyway, the conversation turned to what’s going on this summer.

It’s been hot, in short and even if July has been cooler and rainy in Denmark, May and June were hot and record dry..

And it’s fair to say that, as when I’m asked why, or similar questions by journalists, there is an almost overwhelming temptation to say “we told you so”. I think that’s what Antonio Guttieres is getting at here too.

However, that’s not what I was mostly musing on. Given the apocalyptic heatwaves, strange patterns of warming in the ocean and the Antarctic sea ice loss, it feels a little like end of days.

But pretty much all of these were projected pretty accurately by scientists, even if the timing was a bit off and we’re not entirely sure what is driving that extraordinary downturn in Antarctic sea ice (but do read Zack’s piece linked here, it’s very good).

In many ways, we’re fortunate in Denmark and the rest of rich northern Europe. The worst direct impacts, at least in the near and short term, we can probably adapt to, though it will be expensive. They are mostly engineering challenges with a dollop of social science mixed in. And, we should remember that even in wealthy and well-educated Europe, how heavily climate change impacts us is very much determined by our social class.

However, in the long-term (and I do mean really long-term – on the century to millennia scale), we’re facing something more existential. We’re going to lose a lot of Danish land to sea level rise. Exactly how much will largely be determined over the next 20 to 50 years as there’s a pretty clear relationship between greenhouse gases and melting ice.

But we do have time to prepare for it- and most importantly to have some grown up conversations about our priorities as a society. This is going to require a good bit more social and behavioural science. In the medium term, we will need to prepare for ever more storm surges, but adaptation to coastal flooding also falls into the engineering category.

Of course, these local to regional risks still need dealing with and that is largely why my employer has created the awesome Danish climate atlas – to give accurate but also useful climate information to those who need to plan for the future. I suspect an ever greater part of my job will be focused on producing usable projections and climate service information. This is certainly also something we will focus on in the PRECISE project. Being able to make useful sea level rise projections is about more than identifying if an ice sheet is stable* or not, it’s also about how quickly, how likely and how much it is likely to retreat. As we have also focused on at a regional level in the PROTECT project

So that’s ice sheets and sea level. The tl;dr is, we know they’re melting, we still don’t know by how much and how fast they’ll ultimately melt but we still have time to deal with it, at least in wealthy well educated societies like Denmark,.

There is a whole nother discussion to be had about the global south and less equal societies which I don’t feel confident enough to discuss here.

Where I do think we’re more vulnerable in the shorter and medium term is perhaps surprisingly, food production – and that goes for much of Europe too. It turns out that concentrating large amounts of food production in a few key places might be a big mistake. Especially where those places are vulnerable to drought, heatwaves, over extraction of water, not to mention appalling labour conditions, an over-reliance on groundwater, artificial fertilisers and pesticides.

And then there is some evidence that multiple heatwaves could occur concurrently, threatening food production in compound events across several key regions. Perhaps working out how to make the global food chain less vulnerable to disruption at key points should be more of a focus than it is?

And that’s after the latest banditry from Russia, destroying perfectly good foodstocks and the means to distribute them, has given us a clear wake-up call on the interdependence of human society.

(Anders Puck Nielsen a military commentator has an interesting take on that from a strategic point of view here: https://youtu.be/fvPcPZP-6os which is very interesting for Ukraine watchers)

If I were a wise and concerned government I think I’d be thinking about how exactly we’re going to be feeding our population over the next 5-20 years. Where will be able to produce like Spain and Italy today? Or will diets have to change? How do we persuade people to eat more healthily and ensure that food is equitably spread through society?

This is of course also a part of the job of the other working groups, 2 and 3 of the IPCC – and it’s possibly not just an accident or indeed good lobbying that the new IPCC chair, Jim Skea, is a former WG3 coordinator. Perhaps the IPCC also sees that we have now moved into a new world.

So, these are just some of the things I’m thinking about as I prepare to go back to the office after the summer break next week.

As I observed on Mastodon after the IUGG meeting, and online with this excellent heatmap article. Climate science is entering a new phase. It’s the end of the beginning and it’s time to prepare.

*On the subject of ice sheet stability, Jeremy Bassis has an excellent thread on what this does and does not mean over on Mastodon. Worth checking out

Bringing back the wild to Europe

Today the European Council is debating (behind closed doors), the proposed Nature Restoration Law – there has been heavy lobbying by several EU countries to water down the provisions. I believe this is a mistake and last week I and almost three and a half thousand other scientists signed a petition saying so.

It has now been reopened for signatures. Please do sign if you feel strongly about it. It’s worth a read anyway as the organisers (probably being scientists!) have written out what the agreement means in admirable clarity:

https://umfrage.uni-leipzig.de/index.php/837218?lang=en

Europe is a nature depleted continent already – restoring, or at least preserving what we can is going to be crucial in coming decades. And where Europe leads and sets strict environmental standards, other countries follow.

I am a climate scientist who has become increasingly interested in and concerned about biodiversity. I have had a deep love and sense of wonder about nature since I was a kid – and probably my interest in glaciers and weather and climate have in in part grown out of that. I’m not a biodiversity expert, but I am acutely aware of the impact climate change is already having on the biosphere. It is at a fundamental level very hard to separate climate from biodiversity and probably unwise to try.

In the past I’ve considered it was a scientist’s duty to advise impartially and therefore to be politically completely inactive, I have regretfully come to the conclusion that actually, maybe we as a community do need to push a little more firmly in the direction our science is actually pointing us. Perhaps it is in fact irresponsible not to be involved?

As the great atmospheric chemist and Nobel Laureate Sherwood Rowland once said (in 1986!):

“After all, what’s the use of having developed a science well enough to make predictions, if in the end all we’re willing to do is stand around and wait for them to come true?”

Brodeur, 1986

This quote is something I have thought long and hard about myself. And I’m not the only one in the climate field for sure. If our biodiversity colleagues are also wrestling with this, then I also recommend this brilliant piece by NASA GISS scientist Gavin Schmidt in the Bulletin of Atomic scientists.

The petition I linked to above has been organised by german scientists, experts in ecology and biodiversity. They emphasise:

“Being proactive is thus important. We would therefore appreciate if you found your way of communicating this letter in your surroundings, and help delivering the science to whoever may be interested in it. The purpose is not to lobby but rather to support, to offer help, maybe even mediate where possible.”

We’re scientists and we’re also public servants.

Use us to help guide policy. If scientists are ringing alarm bells, then somewhere there is a fire…