The Danish online popular science magazine is currently running a series on tipping points in the Earth system with a series of interviews with different scientists. They asked me to comment on the extraordinary low sea ice in Antarctica this year. You can read the original on their site here. But I thought it might be interesting for others to read in English the piece which is a pretty fair reflection of my thinking. So I’m experimenting a little with DeepL machine translation which I consider much more reliable that google’s competitor. I have not edited anything in the below!

I have been promising a piece on West Antarctica for a while – which I’m still working on, but hopefully this is interestign to read to be going on with!

A sudden and surprising loss of sea ice in Antarctica could be a sign that we are approaching something critical that we need to prepare for, warns an ice researcher from DMI.

The climate seems to be changing before our eyes.

2023 has seen record high temperatures both on land and in the ocean, which you can read more about in the article ‘Is the climate running out of control like in ‘The Day After Tomorrow’?

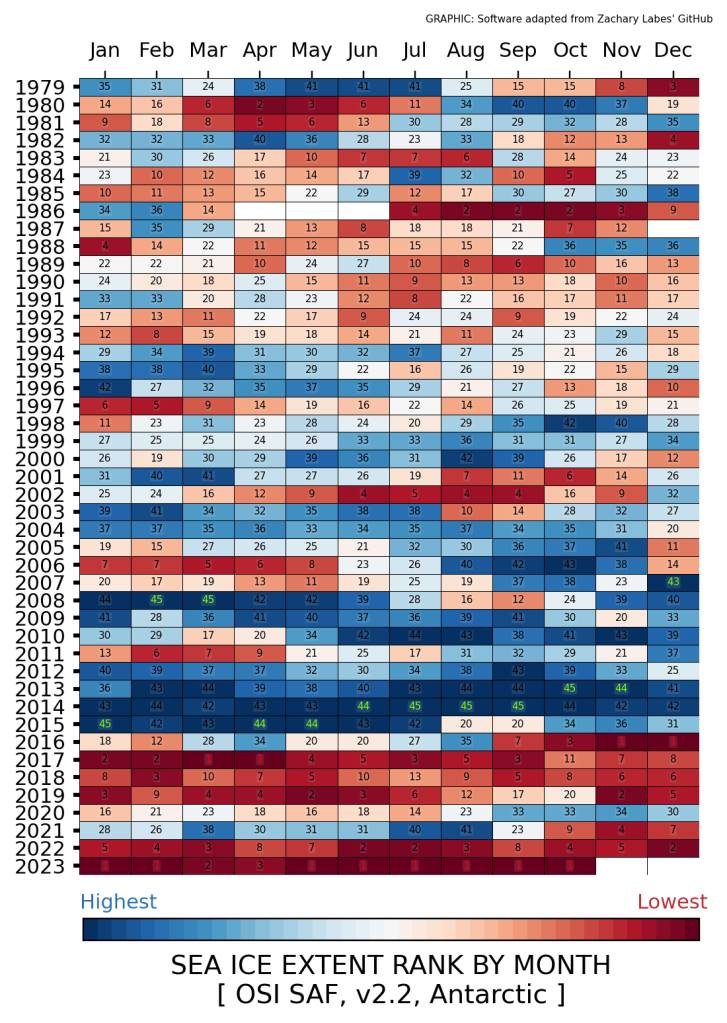

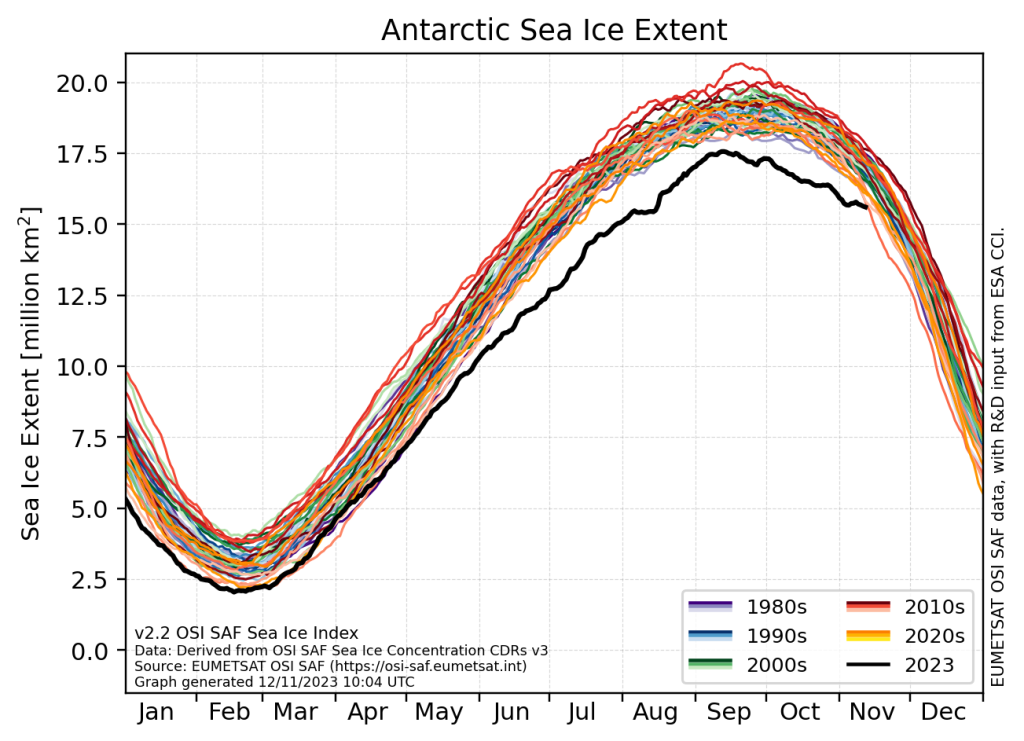

In Antarctica, there has been a sudden, violent and in many ways unexplained lack of sea ice, which normally melts in the summer and re-forms in the winter.

Since then, some of what was lost has been recovered, but when the sea ice peaked in September 2023, 1.75 million square kilometres of sea ice was still missing. This is equivalent to about 40 times the area of Denmark.

This is by far the lowest amount of sea ice ever measured in Antarctica.

“The melting sea ice in Antarctica is not unexpected in itself, because we have long predicted that it would disappear due to global warming,” Ruth Mottram, senior climate researcher and glaciologist at the Danish Meteorological Institute (DMI) tells Videnskab.dk.

The climate seems to be changing before our eyes.

2023 has seen record high temperatures both on land and in the sea, which you can read more about in the article ‘Is the climate running out of control like in ‘The Day After Tomorrow’?

“But to suddenly have a very, very large disappearance like that is a big surprise. We can’t explain why it happened, and our models can’t recreate it either,” she says, but adds that over time, the models are getting closer to reality.

Disturbances in the Earth’s system are probably connected

Videnskab.dk has in a series asked five leading Danish scientists to assess the state of the climate from their chair – in this article Ruth Mottram.

Ruth Mottram is head of the European research project OCEAN:ICE.

The OCEAN:ICE project

The researchers in OCEAN:ICE, led by Ruth Mottram as principal investigator, will take measurements below the ocean surface. This will provide more knowledge about the temperatures in the ocean around Antarctica.

They will also calculate how fast the ice is melting in Antarctica due to ocean processes and warming in the air. They will also investigate what the lack of sea ice means for the rest of the Antarctic system.

Ruth Mottram cites as examples:How does it affect ecosystems? For example, many animals feed on the small crustacean krill, whose life is affected by sea ice. Will more waves now reach the Antarctic ice sheet and perhaps lead to more icebergs and more melting? Will glaciers and icebergs become more sensitive to heat? Or, on the contrary, will less sea ice trigger more snow over the continent, which could even stabilise the glaciers?

More specifically, researchers will focus their efforts on seven areas, which you can read more about on the OCEAN:ICE website.

In the project, researchers will, among other things, take measurements under the sea surface in Antarctica to gain more knowledge about how the ocean and ice interact.

Is melting sea ice linked to warm water in the Atlantic?

In the North Atlantic, sea surface temperatures in some places have been as much as five degrees above normal.

To an outsider, it seems obvious that this could have something to do with melting sea ice.

However, according to Ruth Mottram, the two factors are not necessarily directly related. Sea ice in Antarctica melts from below. Therefore, the temperature at the bottom of the sea is far more important than the temperature at the surface.

“But if there’s one thing I’ve learnt over the past 15 years working at DMI, it’s how interconnected the whole world is. So I think we’re seeing some disturbances throughout the Earth system that are unlikely to be completely independent of each other,” she says to Videnskab.dk.

Ocean Professor Katherine Richardson made the same point earlier in the series. You can read about it in the article ‘Professor: The oceans are warming much faster than expected’.

Lack of knowledge and observations

Ruth Mottram emphasises that far more observations from Antarctica are needed before we can say anything definite about the causes of the rapidly shrinking sea ice, but: “It could indicate that the Antarctic sea ice has a critical tipping point like the Arctic, where for a number of years we see a slow decline year by year, and then suddenly it drops to a new stability where it is very low compared to before.””But we don’t know, because there are parts of the system that we don’t understand and that we haven’t observed yet,” explains Ruth Mottram.

Possible reasons why sea ice is disappearing

Ruth Mottram talks a lot with international colleagues about why the sea ice is currently experiencing a significant decline.

She explains that there are different theories, for example that warmer water from below is coming into contact with the sea ice and melting it from below, and that warmer air may be feeding in from above.

In Antarctica, the direction and strength of the wind has a big impact on the state of the ice (click here for a scientist’s timelapse of how Antarctic weather changes rapidly).

Perhaps the sea ice has been hit by “a very unfortunate event”, where it is both being hit by warm water from below and being affected by weaker winds from changing directions, which is holding back the recovery of sea ice.

Again, more research is needed.

Melting ice also contributes to sea level rise, and the Earth is actually designed so that melting in Antarctica hits the northern hemisphere much harder than melting in Greenland. So, bad news for the ice in Antarctica is bad news for Denmark.

Even more bad news is on the horizon.

The natural weather phenomenon El Niño looks set to get really strong over the next few months. A so-called Super-El Niño will likely only make the world’s oceans even warmer.

“We know that the ocean is going to be really, really important in the future in terms of how fast the Antarctic ice is melting and what that will mean for sea level rise,” says Ruth Mottram.

We can’t just wish the world would look different

The climate scientist does not fear huge increases or a violent change in climate overnight, as depicted in the 2004 disaster film ‘The Day After Tomorrow’. She points out that even abrupt shifts in the Earth’s past climate have occurred over decades or centuries, not a few months or years. Still, Ruth Mottram thinks it makes sense to start talking a little more openly about how we tackle severe sea level rise – which on a smaller scale can still be sudden – and large-scale climate change.

The Antarctic ice sheet is the largest on the planet

The Antarctic ice sheet contains around 30 million cubic kilometres of ice. This means that around 90 per cent of all fresh water on Earth is frozen in Antarctica.

If all the ice sheet in Antarctica melts, the world’s oceans will rise by around 60 metres. Even if we stay within the framework of the Paris Agreement, we risk that melting Antarctic ice from Antarctica will cause sea levels to rise by 2.5 metres.

Ruth Mottram notes that the more we exceed the limits of the Paris Agreement, the faster sea levels rise – and slower if we act quickly and stay close to the set limits of preferably 1.5 and maximum 2 degrees of temperature rise compared to the 1800s.

“The Earth’s climate system may be shifting towards a new equilibrium, which could result in a different world than we have grown up with,” continues Ruth Mottram.

“It is already affecting us and will do so increasingly in the future. That doesn’t mean it will be a total disaster, but we will probably get to the point where we have to adjust our lifestyles and societies.”

“It won’t necessarily be simple or easy to do so, but we can’t just wish for the world to be different than it is,” says Ruth Mottram.

In another article in Videnskab.dk’s climate series, Professor Jens Hesselbjerg Christensen notes that the world’s finance ministers – including Denmark’s – must pull themselves together and find money to slow climate change by, among other things, putting a cap on greenhouse gas emissions.

“We are in the process of allowing future generations to accept that large areas of land will become uninhabitable because the water level rises too much,” he says.

‘Bipolar’ researcher: Keep an eye on Greenland too

In the short term, Ruth Mottram is interested in finding out what the consequences of El Niño will be and how Antarctica will change over the next few years.

But she also has her sights set on Greenland.

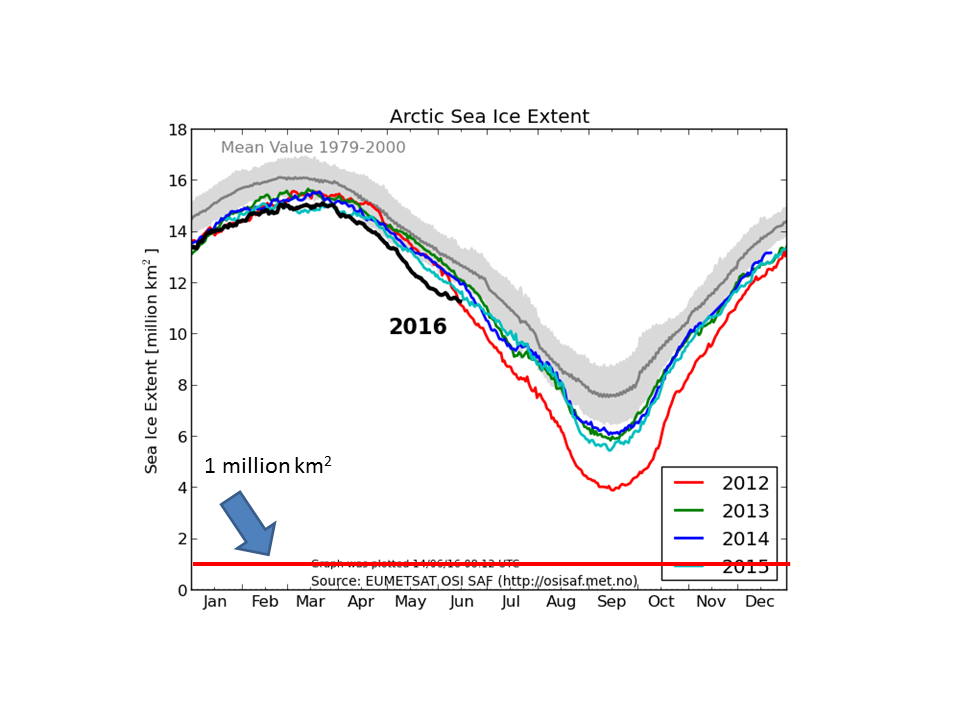

“Because there have been so many weather events elsewhere, it has gone a bit unnoticed that we’ve had a really high melt season in Greenland this year.

“It can give us the opportunity to see very concretely how weather and climate are connected. That’s why the next few years will be really interesting in Greenland,” says Ruth Mottram, who has also conducted research in the Arctic for many years.

The next article in Videnskab.dk’s series on the state of the climate will focus on Greenland.