It’s been a while since I lasted posted anything, not for want of ideas but mainly lack of time. I shall try to catch up over the next few weeks. For now I was inspired to write an ultra-quick post about a very trivial question that came up at work today. I think it really captures how observational meteorology works (or should work).

Today, a colleague, John Cappelen, (also known as Mr. Greenland observational data), happened to mention in passing that on the 15th July this year, the weather station at Summit on the Greenland ice sheet had transmitted back to us in Copenhagen, a temperature observation of 2.5°C. This was during one of the highest melt periods this summer.

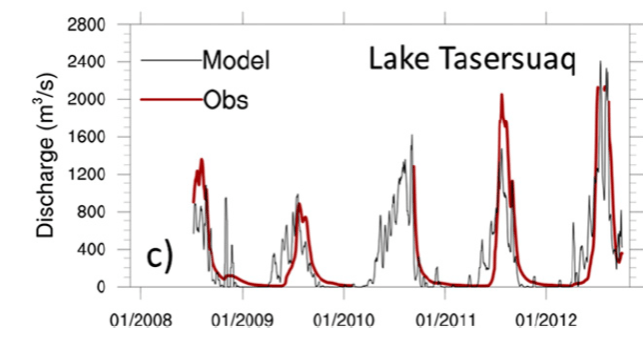

Bearing in mind that Summit Camp is at roughly 3,216m, this is a pretty high measured temperature. In fact it would be rather noteworthy, especially as it occurred on one of the highest melt days of the summer. Temperatures above 0°C at Summit are not unknown and the record, during the famous summer of 2012 when around 95% of the ice sheet surface experienced melt, the water sweeping away a bridge on the Watson River near Kangerlussuaq, was 3.6°C.

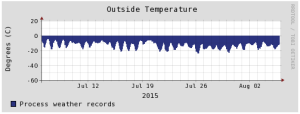

Now, my colleague is a very experienced and careful scientist. He had checked the observations and the temperatures before and after this measurement were well below zero, so, my colleague asked, was there any reason to believe this measurement or can we assume an instrument failure of some kind?

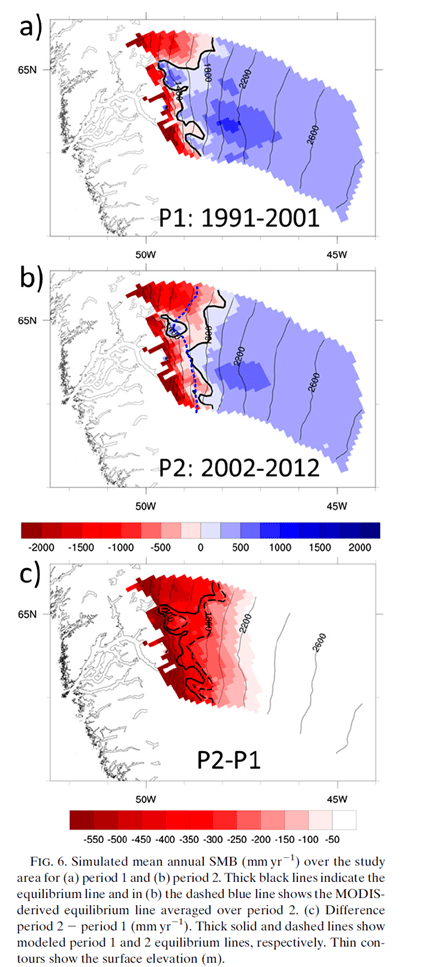

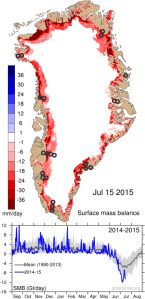

My office mate in the Arctic and Climate Research section and I obligingly had a quick look at our Polar Portal Greenland ice sheet surface plots (see below) and at the melt extent plots that are updated daily on the DMI website. We had to conclude there was no evidence of melt that high on the ice sheet and there was also no reason to believe that a sudden sharp warming had occurred at Summit on this day based on DMI’s own weather forecast. We then turned to check the weather plots, also on the polar portal and based on data from the European Centre for Medium Range Weather Forecasting (the ECMWF – probably the best weather forecast modellers in the world).

Again, the anomaly plots showed rather cold conditions prevailing over the ice sheet during this period, though at the same time very high melt and low surface mass balance from the ice sheet due to the clear skies.

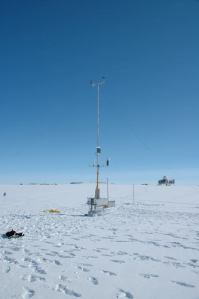

Fortunately, due to the American Summit Camp we have access to a back-up dataset very close to this location and after a quick web search John Cappelen was able to confirm that indeed this measurement was an error as the nearby station has not seen anything like that during the period in question (see right).

This kind of thing happens all the time and is therefore not at all newsworthy or interesting enough to write a publication about. However, when a recent record high temperature in the UK can lead to 2 critical articles in the Daily Telegraph and a particularly vigorous exchange on twitter for Met Office scientist Mark McCarthy, as well as this corrective piece on the Carbon Brief blog, perhaps we should be more vocal about just how careful and critical we as scientists are about observations, including the ones we decide to discard as well as the ones we keep.

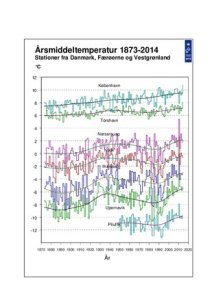

Addendum: I was alerted by this tweet from Gareth Jones, also a Met Office scientist, to some slightly strange cherry picking in the blogosphere of climate records from a couple of DMI stations in Greenland. These have apparently been used to claim no climatic warming trend in Greenland over the 20th Century (I’m not going to link to it).

Anyone who is really interested in the observational data could try checking these reports by Mr Greenland observations himself instead, here is a quick summary: