UPDATE THE MORNING AFTER (21/10/2023): water levels are now falling rapidly to normal and the worst of the gales are past, so it’s time for the clean-up and to take stock of what worked and where it went wrong. It’s quite clear that we had a hundred year storm flood event in many regions, though the official body that determines this has not yet announced it. Their judgement is important as it will trigger emergency financial help with the cost of the clean-up.

In most places the dikes, sandbags and barriers mostly worked to keep water out, but in a few places they could not deal with the water and temporary dikes (filled pvc tubes of water km long in some cases) actually burst under the pressure, emergency sluice gates and pumps could also not withstand the pressure in one or two places.

Trains and ferries were delayed or cancelled and a large ship broke free from the quayside at Frederikshavn and is still to be shepherded back into place.

Public broadcaster DR has a good overview of the worst affected places here.

Water levels reached well over 2m in multiple places around the Danish coast and in some places, water measurements actually failed during the storm..

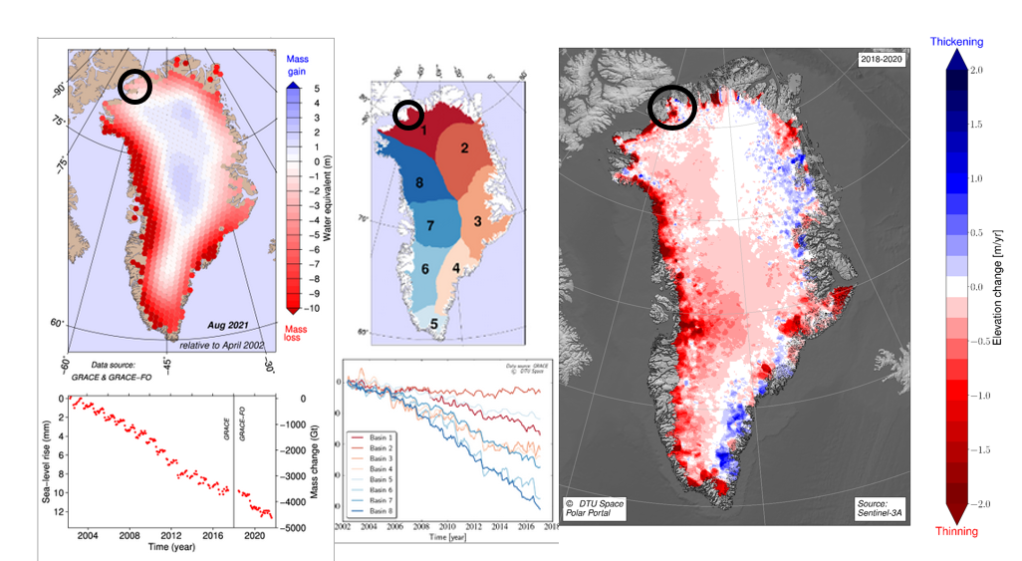

In other places, measurements show clearly that the waters are pretty rapidly declining. So. A foretaste of the future perhaps? We will expect to see more of these “100 year flood” events happening, not because we will have more storms necessarily but because of the background sea level rising. It has already risen 20cm since 1900, 10cm of that was since 1991, the last few years global mean sea level has risen around 4 – 4.5 mm per year. The smart thing to do is to learn from this flood to prepare better for the next one.

But we as a society also to assess how we handle it when a “hundred year” flood happens every other year…

-Fin-

Like much of northern Europe we have been battening down the hatches, almost literally, against storm Babet in Denmark this week. DMI have issued a rare red weather warning for southern Denmark, including the area I often go kayaking in.

From a purely academic viewpoint, it’s actually quite an interesting event, so beyond the hyperbolic accounts of the TV weather presenters forced to stand outside with umbrellas, I thought it was worth a quick post as it also tells us something about compound events, that make storms so deadly, but also about how we have to think about adaptation to sea level rise.

I should probably start by saying that this storm is not caused by climate change, though of course in a warming atmosphere, it is likely to have been intensified by it, and the higher the sea level rises on average, the more destructive a storm surge becomes, and the more frequent the return period!

Neither are storm surges unknown in Denmark -there is a whole interesting history to be written there, not least because the great storm of 1872 brought a huge storm surge to eastern Denmark and probably led directly to the founding of my employer, the Danish Meterological Institute. My brilliant DMI colleague Martin Stendel persuasively argues that the current storm surge event is very similar to the 1872 event in fact, suggesting that maybe we have learnt something in the last 150 years…

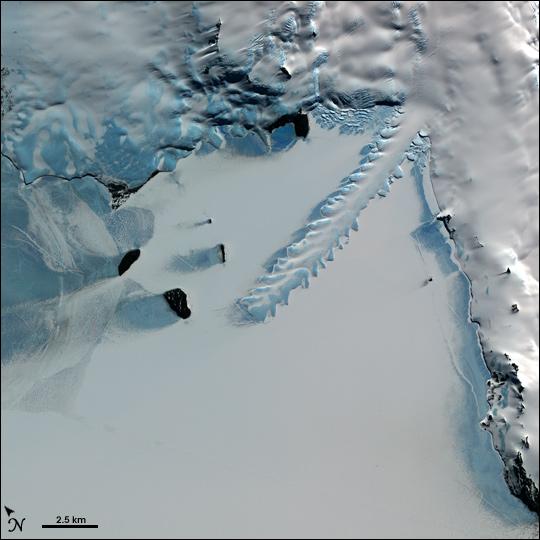

Xylografi, der viser oversømmelsens hærger på det sydlige Lolland

År: 1872 FOTO:Illustreret Tidende

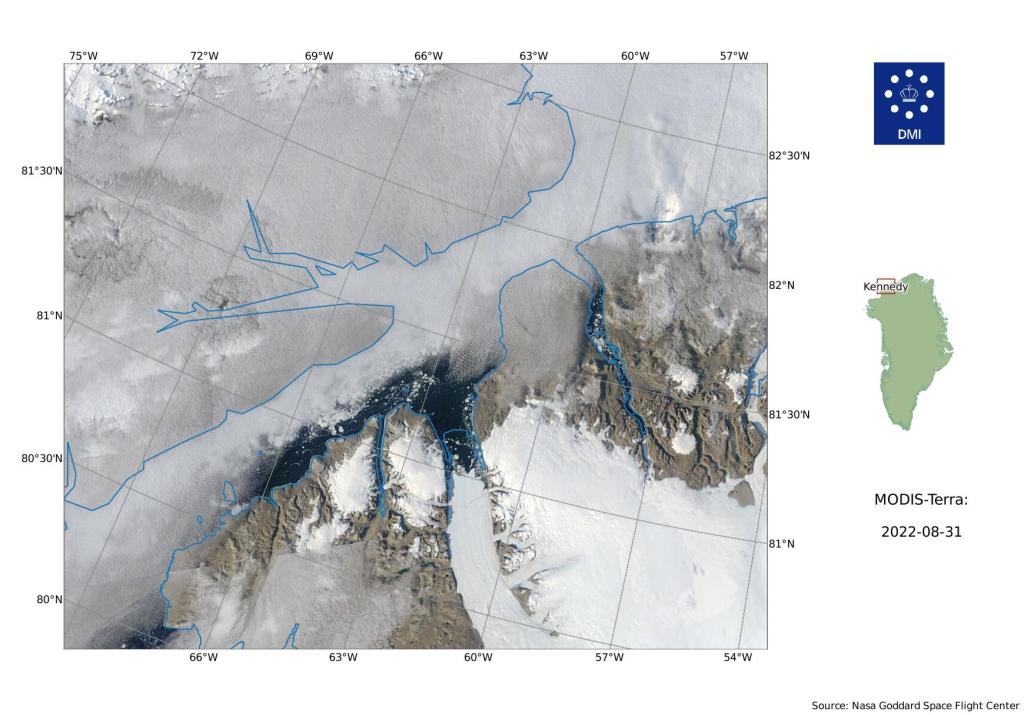

However, back to today: the peak water is expected tonight, and the reason why storm surges affect southern and eastern Denmark differently to western Denmark is pretty clear in the prognosis shown below for water height (top produced by my brilliant colleagues in the storm surge forecasting section naturally) and winds (bottom, produced by my other brilliant colleagues in numerical weather prediction):

Basically, the strong westerly winds associated with the storm pushed a large amount of water from the North Sea through the Kattegat and past the Danish islands into the Baltic Sea over the last few days. Imagine the Baltic is a bath tub, if you push the water one way it will then flow back again when you stop pushing. Which is exactly what it is now doing, but now, it is also pushed by strong winds from the east as shown in the forecast shown above. These water is being driven even higher against the coasts of the southern and eastern danish islands.

The great belt (Storebælt) between the island of Sjælland (Zealand) and Fyn (Funen) is a key gateway for this water to flow away, but the islands of Lolland, Falster and Langeland are right in the path of this water movement, explaining why Lolland has the longest dyke in Denmark (63km, naturally it’s also a cycle path and as an aside I highly recommend spending a summer week exploring the danish southern islands by bicycle or sea kayak, they’re lovely.). It’s right in the front line when this kind of weather pattern occurs.

These kind of storm surges are sometimes known as silent storm surges by my colleagues in the forecasting department because they often occur after the full fury of the storm has passed. I wrote about one tangentially in 2017. This time, adding to the chaos, are those gale force easterly winds, forecast to be 20 – 23 m/s, or gale force 9 on the Beaufort Scale if you prefer old money, which will certainly bring big waves that are even more problematic to deal with that a slowly rising sea, AND torrential rain. So while the charts on dmi.dk which allow us to follow the rising seas (see below for a screengrab of a tide gauge in an area I know fairly well from the sea side), water companies, coastal defences and municipalities also need to prepare for large amounts of rain, that rivers and streams will struggle to evacuate.

In Køge the local utilities company is asking people to avoid running washing machines, dishwashers and to avoid flushing toilets over night where possible to avoid overwhelming sewage works when the storm and the rain is at the maximum.

This brings me to the main lessons that I think we can learn from this weather (perhaps super-charged by climate) event.

Firstly, it’s the value of preparedness, and learning from past events. There will certainly be damage from this event, thanks to previous events, we have a system of dykes and other defence measures in place to minimse that damage and we know where the biggest impacts are likely to be.

Secondly, the miracle, or quiet revolution if you will, of weather and storm forecasting means we can prepare for these events days before they happen, allowing the deployment of temporary barrages, evacuations and the stopping of electricity and other services before they become a problem.

This is even more important for the 3rd lesson, that weather emergencies rarely happen alone – it’s the compound nature of these events that makes them challenging – not just rising seas but also winds and heavy rain. And local conditions matter – water levels in western Denmark are frequently higher, the region is much more tidally influenced than the eastern Danish waters. This is basically another way of saying that risk is about hazard and vulnerability.

Finally, there are the behavioural measures that mean people can mitigate the worst impacts by changing how they behave when disaster strikes. Of course, this stuff doesn’t happen by itself. It requires the slightly dull but worthy services to be in place, for different agencies to communicate with each other and for a bit of financial head room so far-sighted agencies can invest in measures “just in case”. We are fortunate indeed that municipalities have a legal obligation to prepare for climate change and that local utilities are mostly locally owned on a cooporative like basis – rather than having to be profit-making enterprises for large shareholders..

This piece is already too long, but there is one more aspect to consider. The harbour at Hesnæe Havn has just recorded a 100 year event, that is a storm surge like this would be expected to occur once ever hundred years, in this case the water is now 188cm. The previous record of 170cm was set in 2017. We need to prepare for rising seas and the economic costs they will bring. The sea will slowly eat away at Denmark’s coasts, but the frequency of storm surges is going to change – 20cm of sea level rise can turn a 100 year return event into a 20 year return event and a 20 year return event into an ever year event.

We need to start having the conversation NOW about how we’re going to handle that disruption to our coastlines and towns.